May 3, 2011

Presented by:

Steven Romick

Managing Partner, First Pacific Advisors, LLC

John and Whitney were kind enough to ask me to address this Congress in 2009 and 2010. I graciously begged off, choosing instead to focus on investing our client‘s capital at a time that afforded good opportunities. Now, sadly, I‘ve got all the time in the world. I figured penning my comments just might keep me out of trouble, and yet, I found preparing my thoughts challenging. I realized that as to the future, I really have no idea. With regards to the present, a lack of clarity – and the past just conjures disappointment. Although I never really know what is coming down the road, we usually find gratification uncovering investments amidst the rubble of the abandoned – something sorely lacking today. It does beg the question as to what you might hope to glean from my remarks. I‘ve been asked to discuss one or two investments at a point when the stock market has just about doubled in the past two years. That feels a little bit like asking me to ski Vail in August. So first, I‘d like to talk about how we ended up on this mountain, and then how we‘re picking our way down.

The fact that the U.S. finds itself in its current predicament really ticks me off. Cathartic moments and beneficial change can occur after experiencing great pain. As a nation, we had a chance following the financial crisis, but blew it. Worse still, the pain of ‗08 seems to have been forgotten in ‗11, leaving anxious complacency in its place. An oxymoron though it may be, it won‘t be the first time that people act one way, despite feeling another. Some investors may prefer safety, but when faced with paltry cash yields, they quickly embrace riskier alternatives. The Mexican government took advantage of this last fall, selling $1 billion of 100-year government bonds to yield 6.1%.

I don‘t know many people who are real happy about their portfolios today, yet they seem to be taking it on faith that what caused the not-so-distant market meltdown, will not be repeated because the government has taken the necessary measures. I have less faith that people who couldn‘t see a bubble forming and didn‘t observe it when it was here, can ameliorate the situation, and then prevent another bubble. And so I‘m left with the belief that we have a period of respite, a calm moment between two crises. I wish I could tell you the origin, timing, and magnitude of the event that will cause the next economic dislocation and, with it, investment opportunity – but I can‘t. We always have a healthy respect for what we don‘t know, so we continually hope for the best, while preparing for the worst. Alexandre Dumas wrote, ―All human wisdom is summed up in two words – wait and hope.‖ At this time, we are doing both.

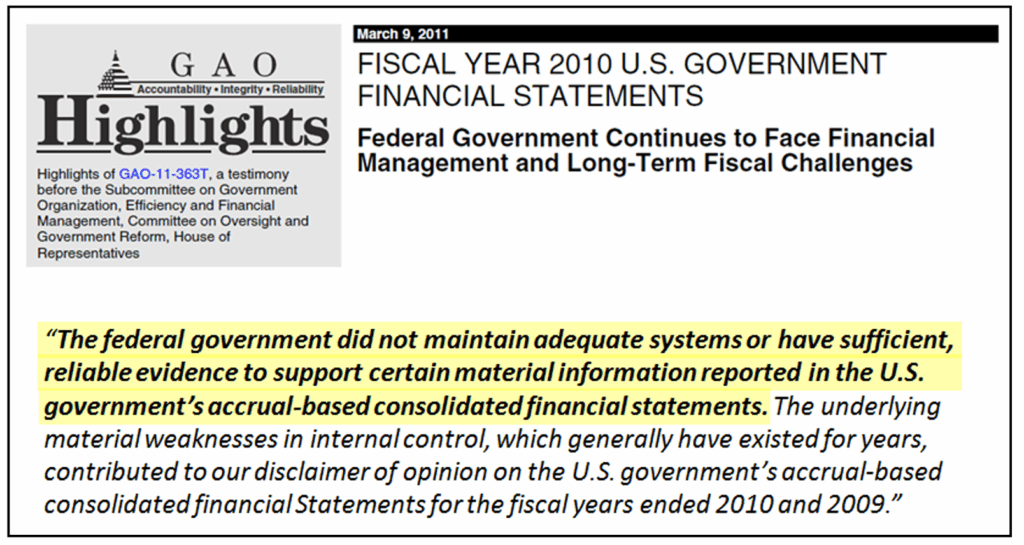

In trying to understand where we are with respect to the economy, we depend on government data, but it‘s not easy to have confidence in the numbers. The General Accounting Office, effectively the U.S. government‘s auditor, has this to say about the latest financial statements, ―…The federal government did not maintain adequate systems or have sufficient, reliable evidence to support certain material information reported in the U.S. government‘s…financial statements.‖ And it goes on, ―The underlying material weaknesses in internal control…which…have existed for years, contributed to our disclaimer of opinion…‖ So when the government says there isn‘t inflation, you really have to take it on faith – and be in perfect health, not need to eat, and walk to work. They are clearly talking their book.

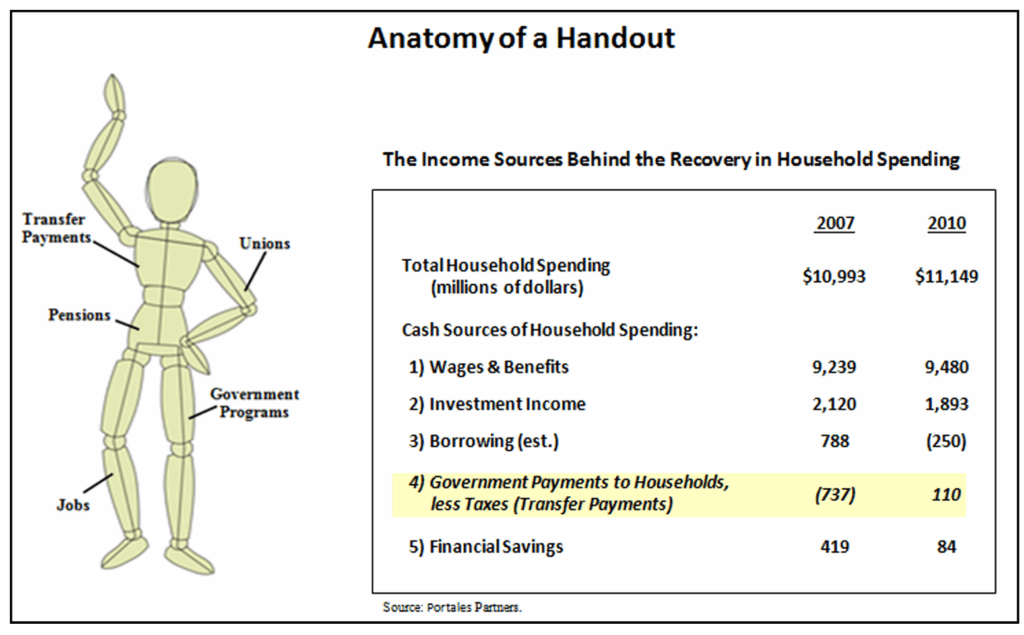

Not only do we believe that inflation is higher than what‘s reported, but we also have to take their word for it when they tell us that the economy is doing well. More than 40% of the population now lives in a household receiving some government benefits. And, there has been an increase of almost $850 billion in Transfer Payments in the last three years, a 6% benefit to the economy over that time. In addition, the government now employs 22.3 million people, a 1.5 million increase in the last decade; while 4.5 million jobs have been lost in goods-producing industries.

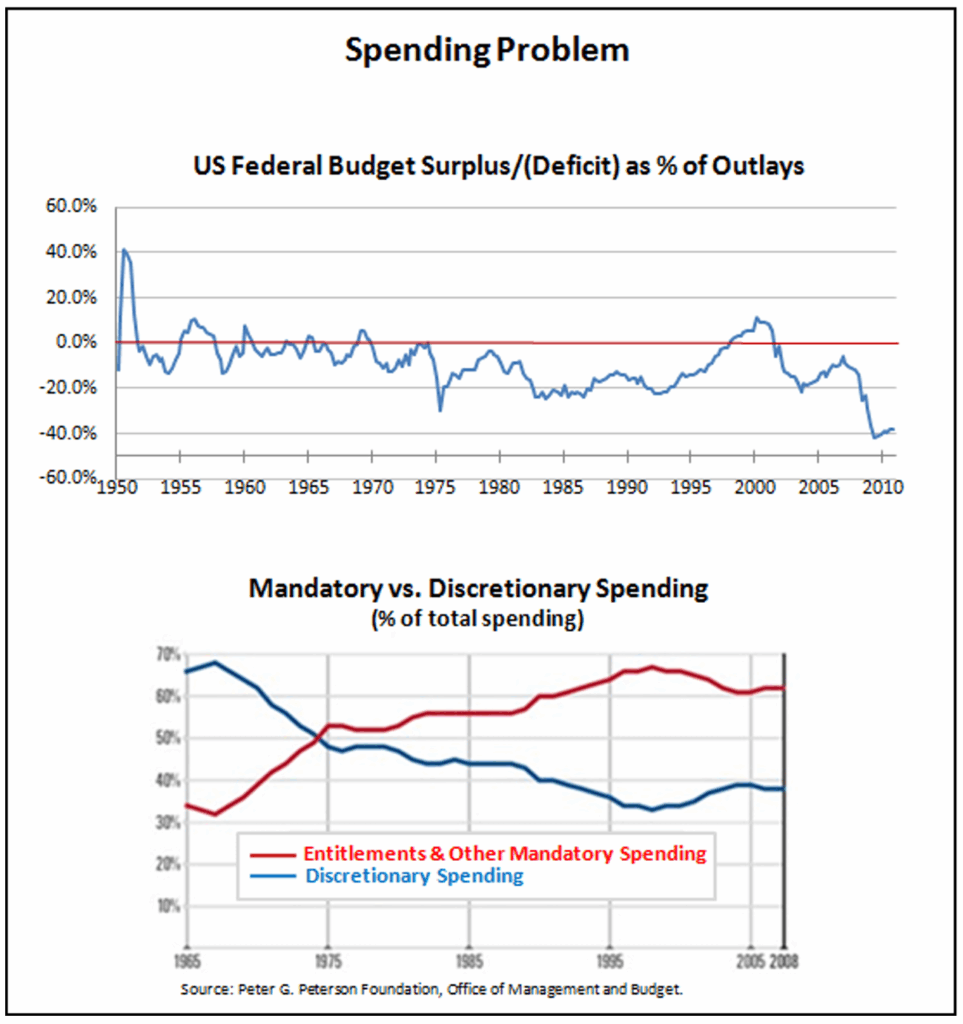

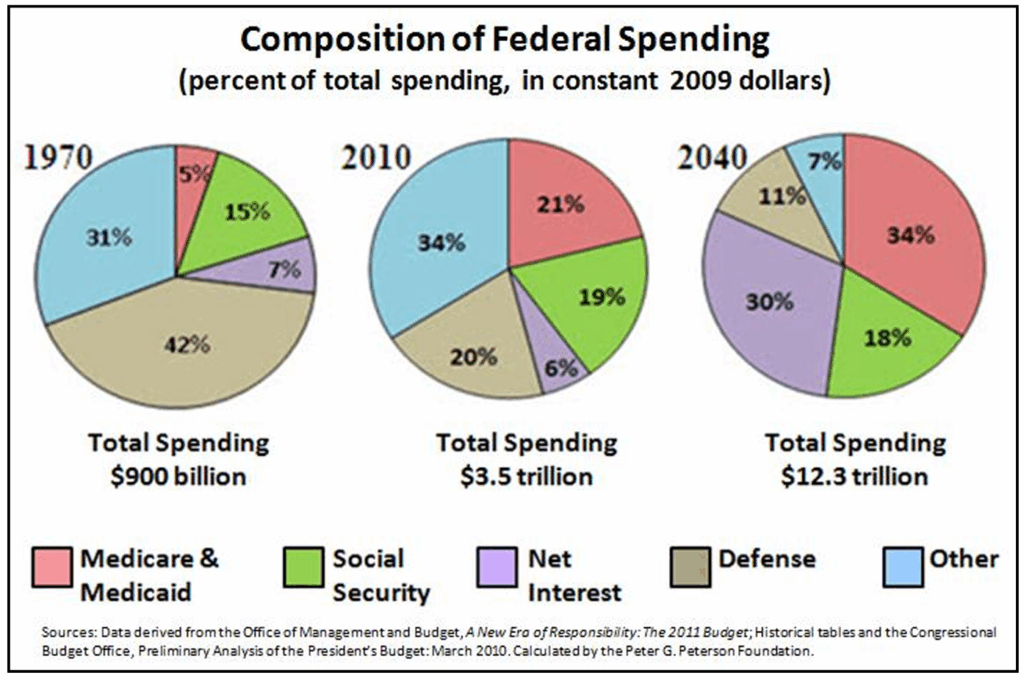

We have a spending problem. We live beyond our means. The U.S. government currently borrows more than 40% of its outlays. It‘s very easy to spend up to improve your lifestyle, but psychologically quite hard to spend less when necessity dictates. Mandatory spending keeps increasing, at the expense of the discretionary. Balancing the budget is impossible when just 16% is on the table, as was the case with President Obama‘s budget proposal earlier this year that failed to address the remaining 84%, comprised of Entitlements, Defense, and Interest Expense. If any of us had to cut spending in order to make ends meet, all expenses would be considered, even those we might have viewed as untouchable in better times.

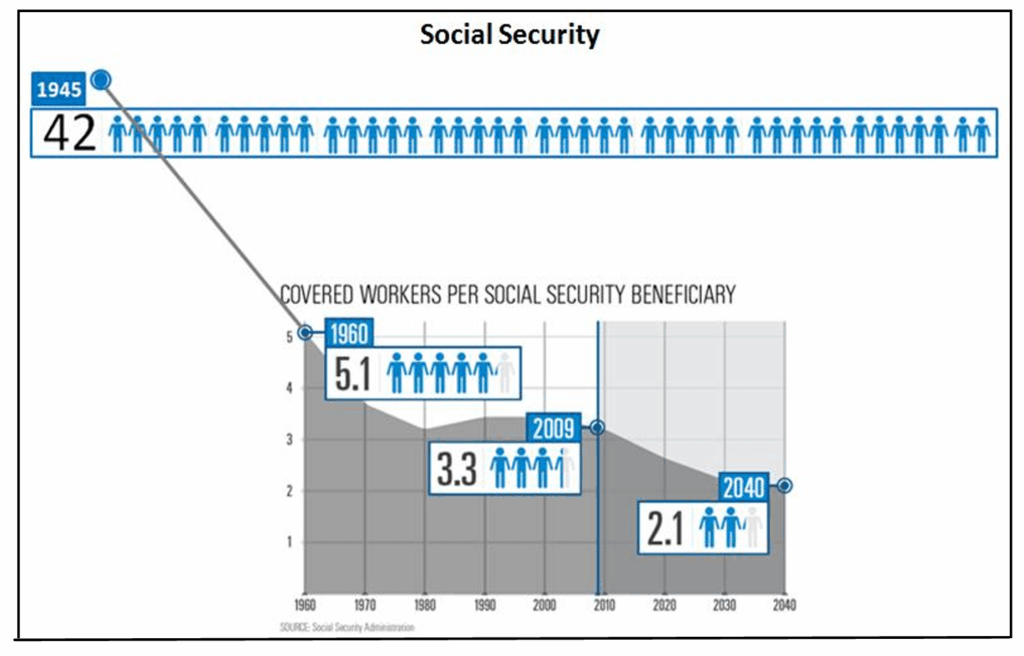

As an example of unchanging rigidity, let‘s take a look at Social Security. It‘s a program that has been held up on a pedestal for far too long, and it‘s gradually morphing from an Entitlement program to Welfare. The world changes and we‘ve got to change with it. When Social Security was created in 1935, an individual could begin to collect benefits at age 65. At the time, the average life expectancy was just 62 years, so not everyone collected. We are now expected to live until age 78, but get to retire at 67. It‘s a great deal – work an extra two years and gain fourteen years of subsidized living. It must be the new math that allows 17% of the population to collect benefits with just three workers supporting every retiree compared to the 1940s, when just 1% received benefits that were being funded by more than forty workers per retiree. I‘m not suggesting that we do away with Social Security, just that it not provide more than originally intended. Our Social Security program serves as a glaring example of original intentions gone awry. We could similarly look at other federal and state programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, unemployment, and public pensions.

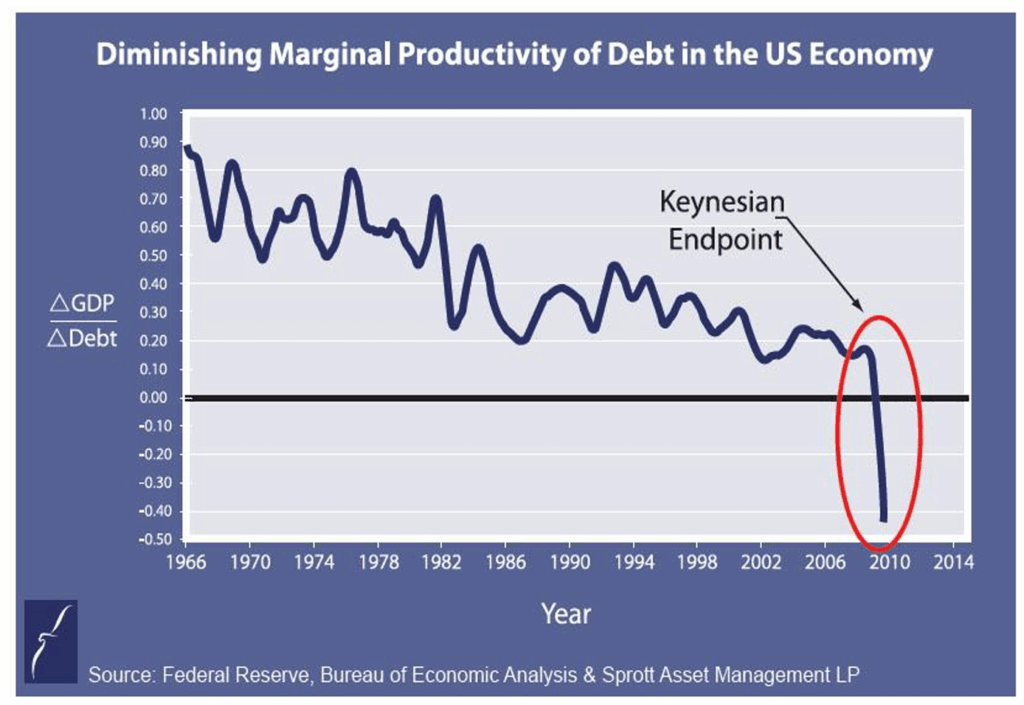

Unbridled spending has led to a debt problem, with total government debt now at about 100% of GDP. How can Americans find themselves limited in their borrowing capacity by both circumstance and desire, but – as a nation, we can keep borrowing? What we can‘t do individually, we can do collectively? The constitutional phrase isn‘t ―”We and the People.” We borrow obscene amounts of money and all we have to show for it is a successively diminishing return on investment. We have watched our returns decline – as measured by the change in GDP versus the change in debt – for each decade beginning with the 1950s, from 73% down to just 17%. No different than a corporation, the government cannot destroy its balance sheet and yet still become more productive.

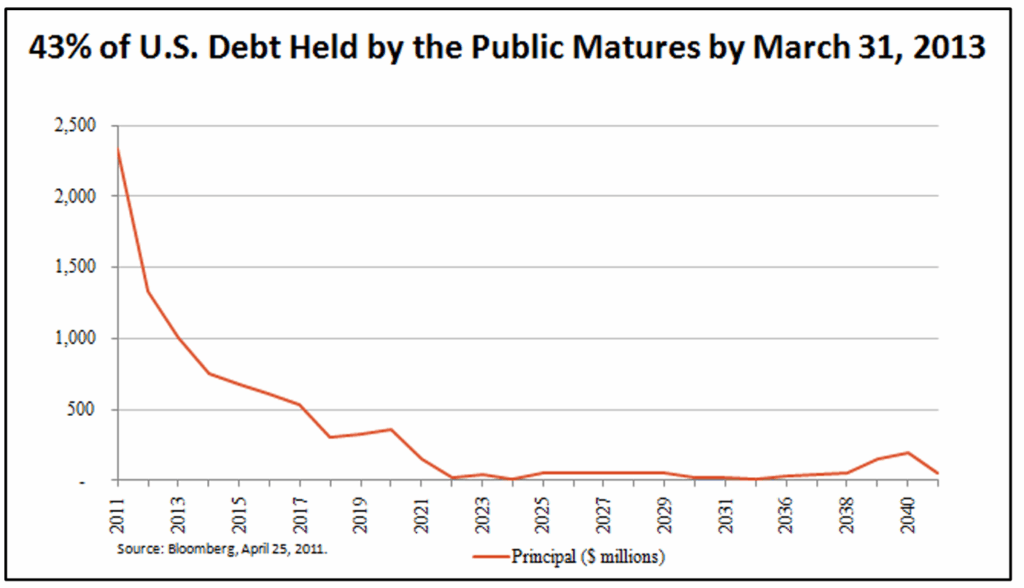

The debt feels manageable, but that‘s because its cost is artificially low. Not only do foreign parties continue to buy our debt to keep the party going, but our government has also created artificial Treasury demand through its Quantitative Easing, and by borrowing short. As a result, we now have 43% of the public portion of our national debt maturing inside of two years.

This leaves interest expense as a percent of outlays at just 6%, less than where we were forty years ago. The problem has been ―solved‖ in both the numerator and denominator. Rates are artificially low and the budget is larger per capita, even when adjusted for inflation.

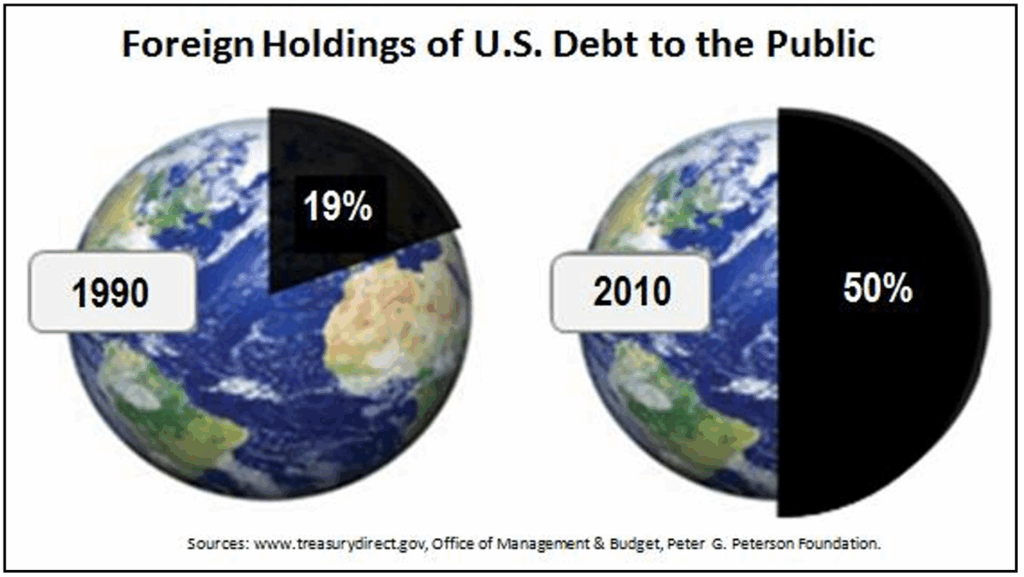

We now have to continue to convince our lenders that the dollars we give them at maturity are as good as the ones we‘re borrowing today. I can‘t figure out who would buy 30-year U.S. Treasury debt at 4.5%, let alone 10-year bonds at 3.4%, but our future course will be determined, in part, by these parties, and particularly by the international community that now owns 50% of our outstanding debt.

The Congressional Budget Office‘s (CBO) sanguine inflation and interest rate projections breed complacency among both elected officials and the general public. The CBO‘s non-partisan projections call for CPI to average just 2.0% between now and 2021, hitting a peak of 2.3%. The borrowing cost assumptions are similarly hopeful. The budget office expects the 10-year Treasury bond to average 4.8%, topping out at 5.4%. Even with such dangerously optimistic projections for interest rates (and most likely for total government debt), the CBO still projects that in the next decade our nation‘s interest expense will exceed what we currently spend on defense.

As a result, we expect interest rates will be higher in the future, possibly significantly higher. It is distressing to think that a five percentage point increase in our debt would cause interest expense to increase as a percentage of the budget from its current 6% to 21%, crowding out other necessary spending and forcing austerity measures that will lower our quality of life through reduced safety, worsening education, insufficient infrastructure, and more – and this is without taking into account the expected increases in our national debt.

The longer the government‘s spending spigot remains open, the more likely the negative outcome. We seem to be confusing medicine with narcotic. Things feel good until we try to wean ourselves. I fear the withdrawal. We know government outlays as an engine of growth can‘t be sustained. We know the traditional economic cycle is now in a transiently altered state. If we don’t allow interest rates to seek a more normal level and prices to find to their natural floors, we can‘t comfortably know what our downside is. But maybe that’s the point ‒ keep things going until it becomes someone else‘s problem. How else does one explain the malpractice of treating the symptom but not the disease? Under the circumstances, we doubt the current recovery is self-sustaining, which leads us to the conclusion that our economy is merely between crises, and that our children will pay for the sins of their fathers.

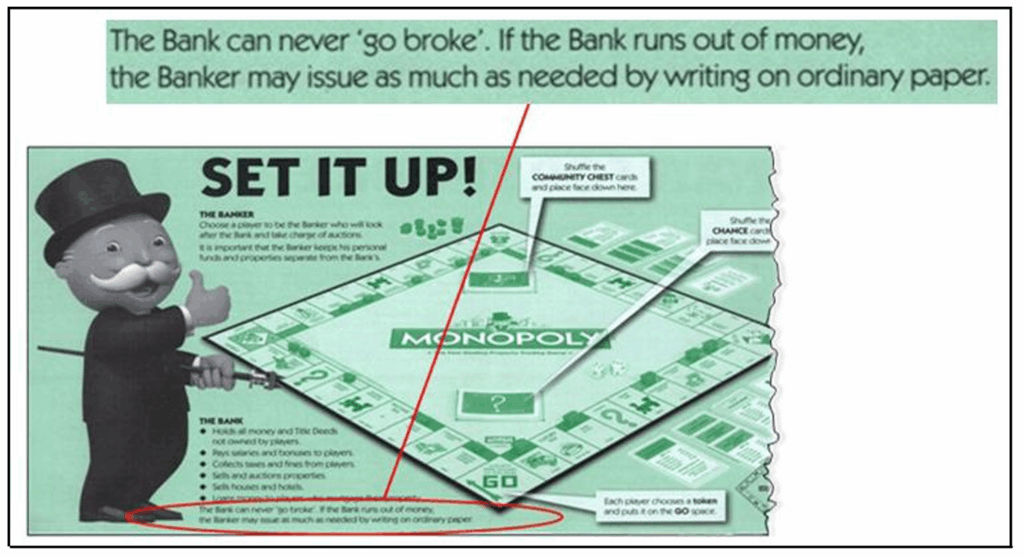

Who said, ―The Bank can never go broke‘. If the Bank runs out of money, the Banker may issue as much as needed by writing on ordinary paper” If not, who said it? Who does it sound like? From the leading econometrics firm of Parker Brothers, the little white-haired guy with the top hat….

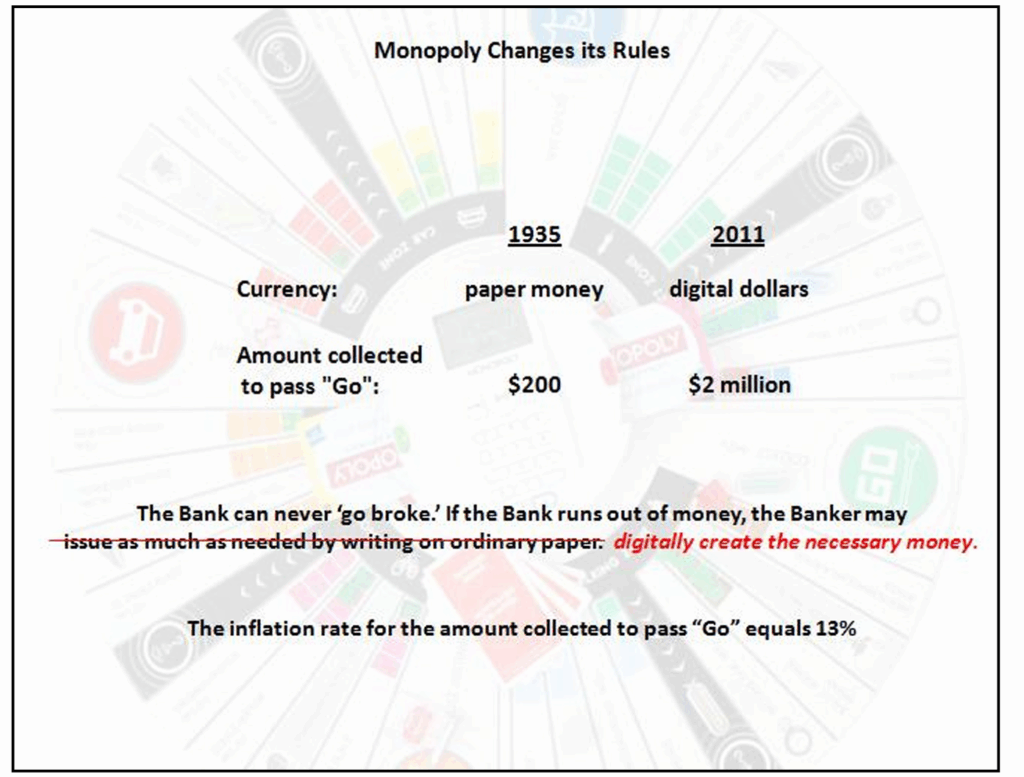

Coming under the heading, ―”Truth is Stranger than Fiction,” Monopoly recently released the updated edition. The now round board game has some significant ―improvements.

Some of the changes (I kid you not) are the elimination of paper money, and when you pass “Go” you will now collect $2 million. What does this 13% rate of inflation in the amount received for passing “Go” portend? I guess we should now change the rules to “The Bank can never ‘go broke‘. If the Bank runs out of money, the Banker may digitally create the necessary money.”

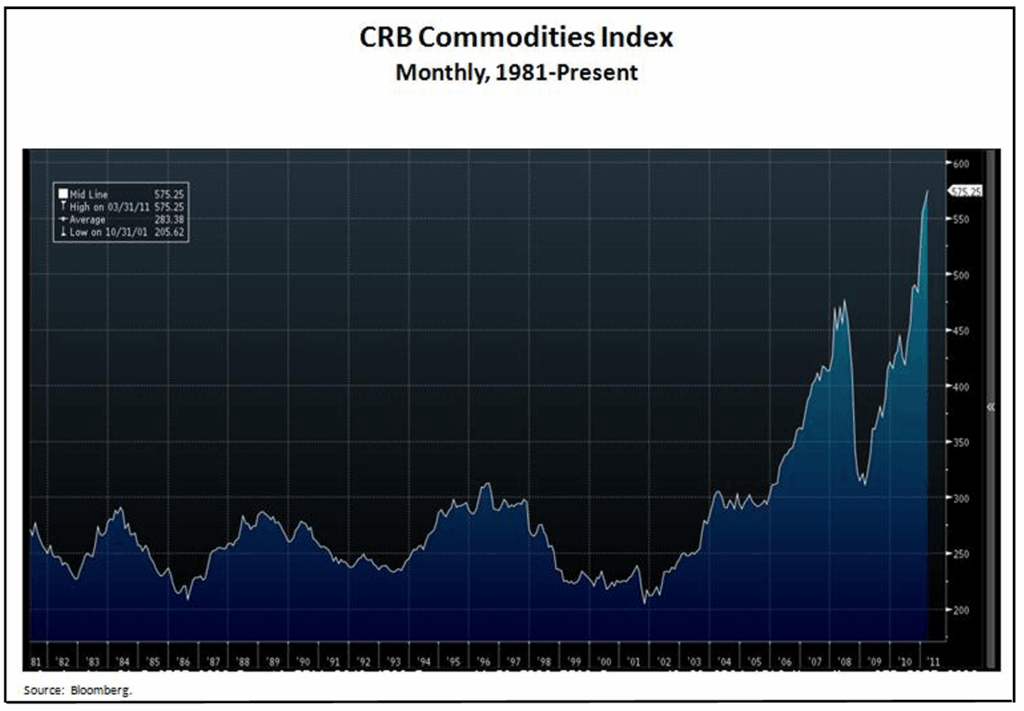

Parker Brothers isn‘t alone in seeing inflation, other signs, particularly commodities, are apparent.

We see an inflation warning light blinking a cautionary yellow, but we also appreciate that its color won‘t slowly change to amber, and then to red. Whenever higher inflation hits, it will happen more quickly than expected. We find it hard to imagine that this unprecedented increase in our monetary base can ultimately unfold any differently.

Our investments take this into consideration, but more for protection than opportunity. A refrain oft used at FPA is that, “sometimes returns are generated not by what you own, but by what you don‘t.”

With corporate margins near highs, we fear their compression. With rates bound to increase, we wonder what might happen to P/E multiples. When shorting with inflation heading higher, we fear being nominally right, but real wrong. And, we are anxious about the longer term prospects for the U.S. dollar. Cash has therefore built by default in our portfolio; and yet, we also fear inflation eroding its value. One of our strategies is to shift our focus to larger, quality businesses, with more exposure to foreign revenue sources and the ability to grow unit volume and increase prices. This is not to say we find abundant investment opportunities.

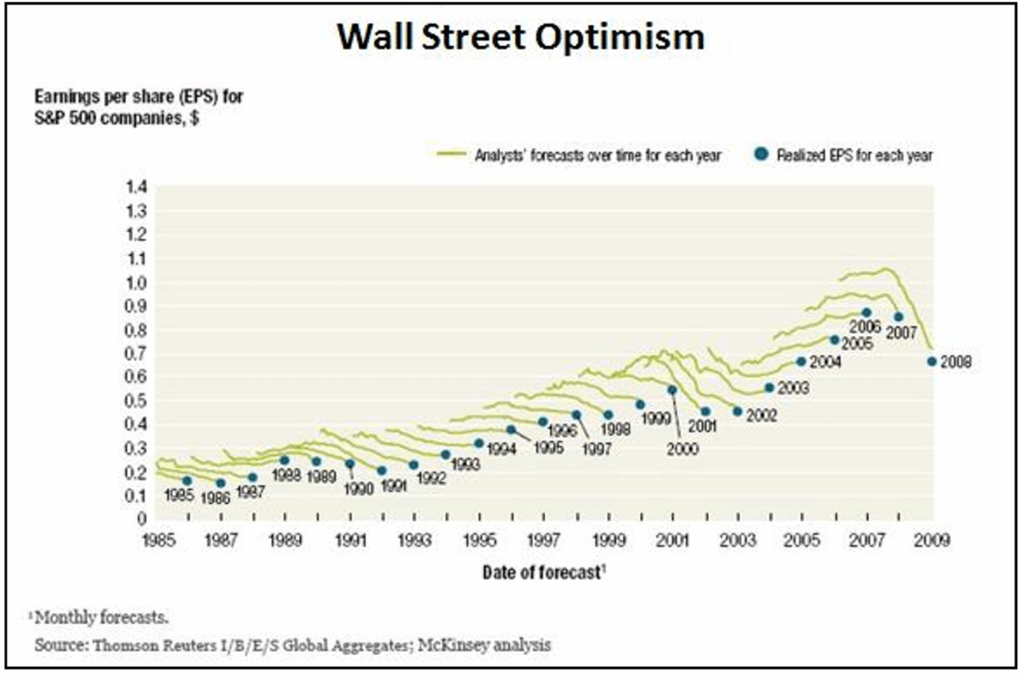

But, if you listen to Wall Street, there‘s always opportunity. But if that‘s the case, why do most fail in their mission?

In a chart that looks eerily similar to the prior slide, Wall Street estimates generally run to the sweetness and light. Just once in these twenty-four years did earnings at the end of the year exceed what analysts had projected at the beginning of the year.

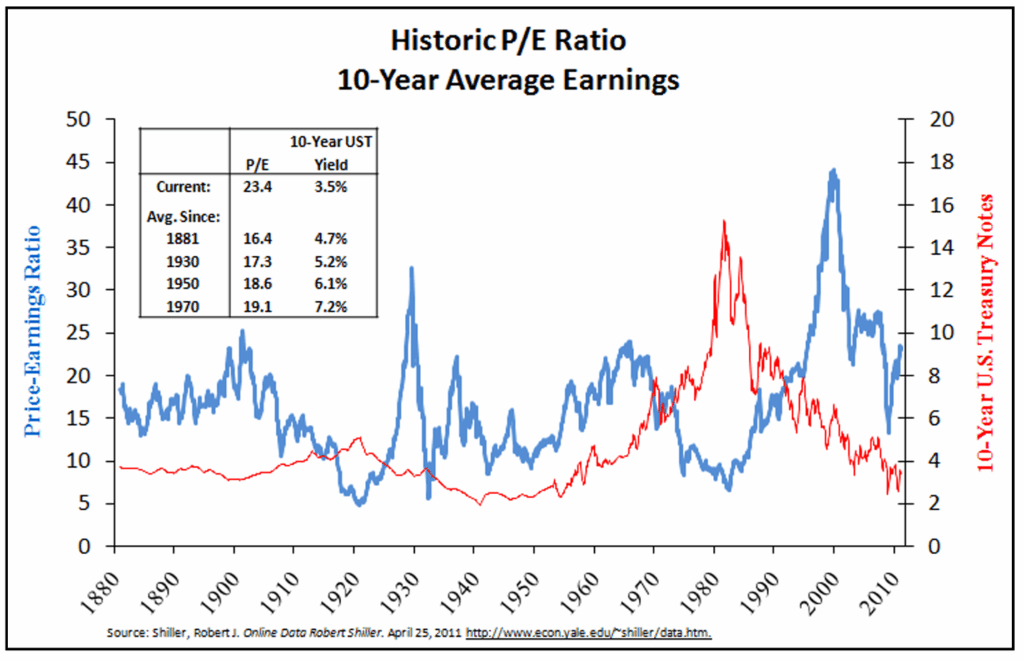

Therefore, when considering market valuation, we prefer to look at measures smoothed over time. Using 10-year average earnings as the denominator, looking at the blue line, you can see that the stock market now trades at a 23x earnings – 36% above average. This can be explained by lower than average interest rates, the red line, with the 10 year U.S. Treasury Bond at just 3.5%, 33% below average.1

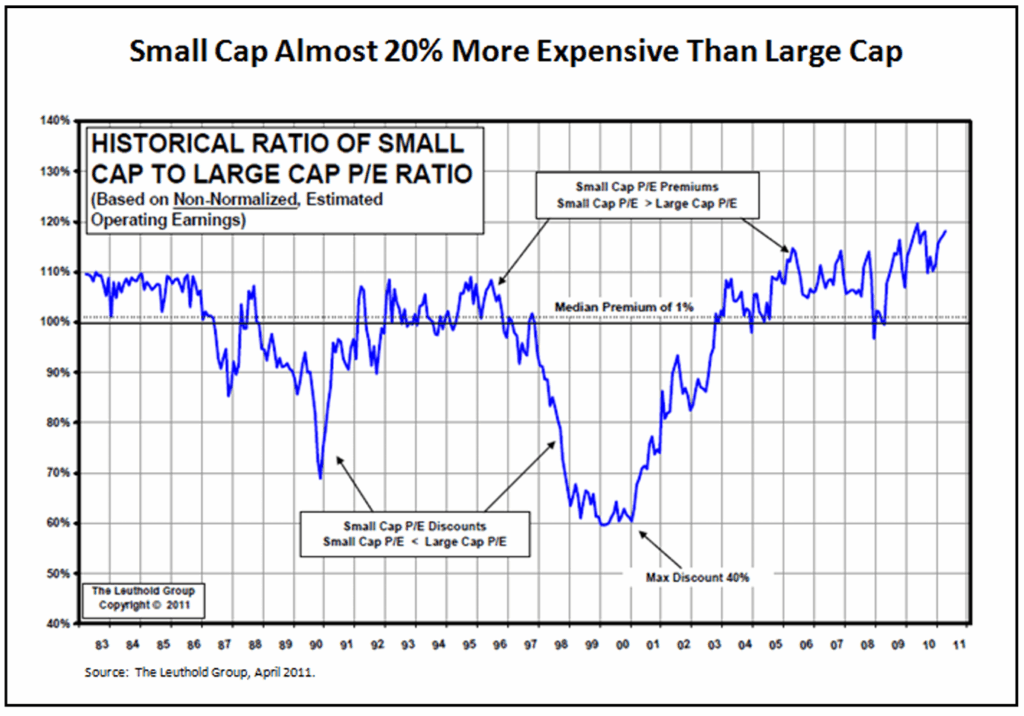

But there are markets within markets. Small cap stocks are almost 20% more expensive than large cap – and thus our increased exposure to the latter – a far cry from the late 1990s, when smaller companies traded at a 40% discount to their larger brethren and our portfolios were heavily tilted to small-cap.

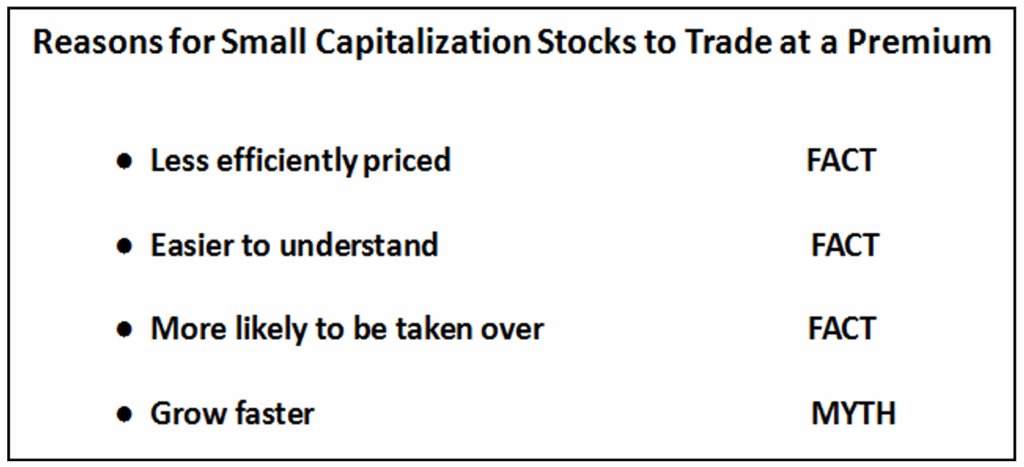

There are a number of reasons that might justify the premium valuation accorded to small-caps. Smaller companies generally have fewer Wall Street analysts following them, making them less efficiently priced, particularly when bad news hits and there is less liquidity for the sellers. Given that they have fewer divisions, they can frequently be easier to understand. They are more likely to be acquired. And, many believe they grow faster. This last point, however, is myth.

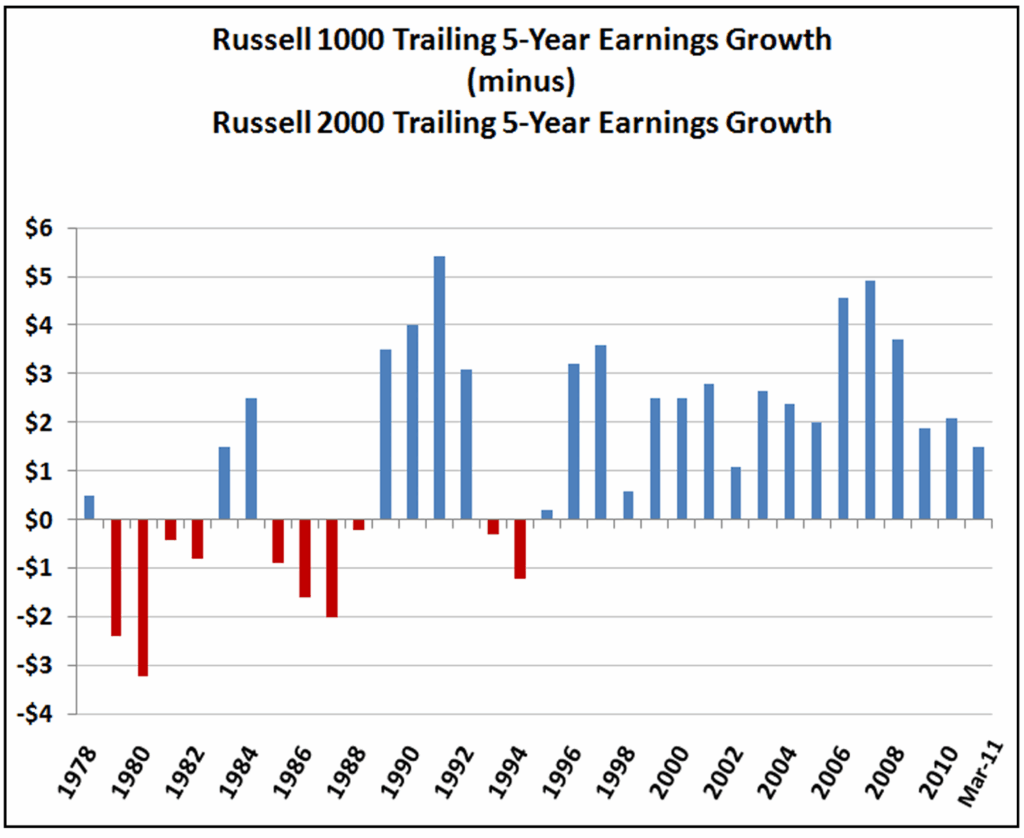

Using the Russell 1000 and Russell 2000 indices as proxies for large- and small-cap companies and comparing their trailing 5-year earnings growth, you can see that it has been sixteen years since small companies last grew faster than their big brothers. Part of the reason, we suspect, is that larger businesses have more sales coming from overseas and thus have the benefit of faster growth in those markets. We don‘t see this being different in the foreseeable future, and we have therefore continued to increase our ownership of larger businesses. Admittedly, this causes us to be short M&A – a negative should the private equity market return to life.

We have positioned our portfolio mindful of the over-priced nature of small-cap stocks, the prospect of higher inflation, and the potential for better growth overseas. Our largest sector exposure continues to be energy, where earnings should not be unduly impacted in an inflationary environment. Our largest position is an insurance broker whose revenues go up commensurate with the insured value of the buildings underwritten, but isn‘t dependent on inflation. And we have a host of special situations that we feel would benefit from inflation. We‘ve purchased subprime whole loans from the likes of Citigroup, Rescap, and GMAC at 45 cents on the dollar, funded a private REIT that invests in farmland, and made a 3-year loan to fund the completion of an office building in the Southeastern U.S. for a low teens IRR.

One company that falls into the category of big (though it lacks the international component we‘ve sought), is CVS Caremark. The pharmacy companies are well-positioned to benefit from a number of macro trends. We prefer investments where the wind is at our backs and we believe that‘s the case here.

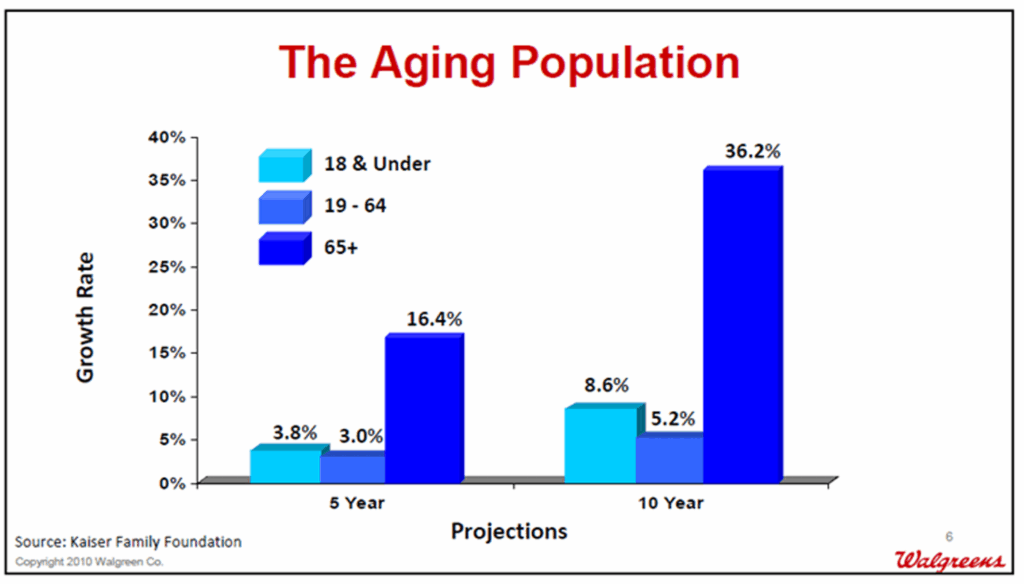

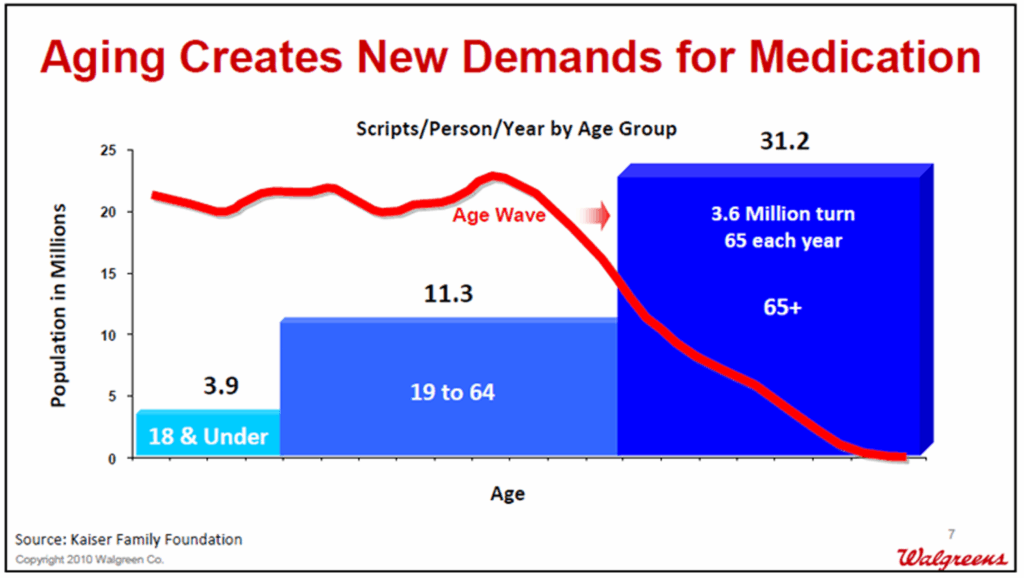

The population of older people is growing more quickly than the younger age groups, and this accelerated aging of our population will drive pharmacy utilization.

The 65+ cohort has almost 3x the number of prescriptions filled per year as the 19-64 cohort.

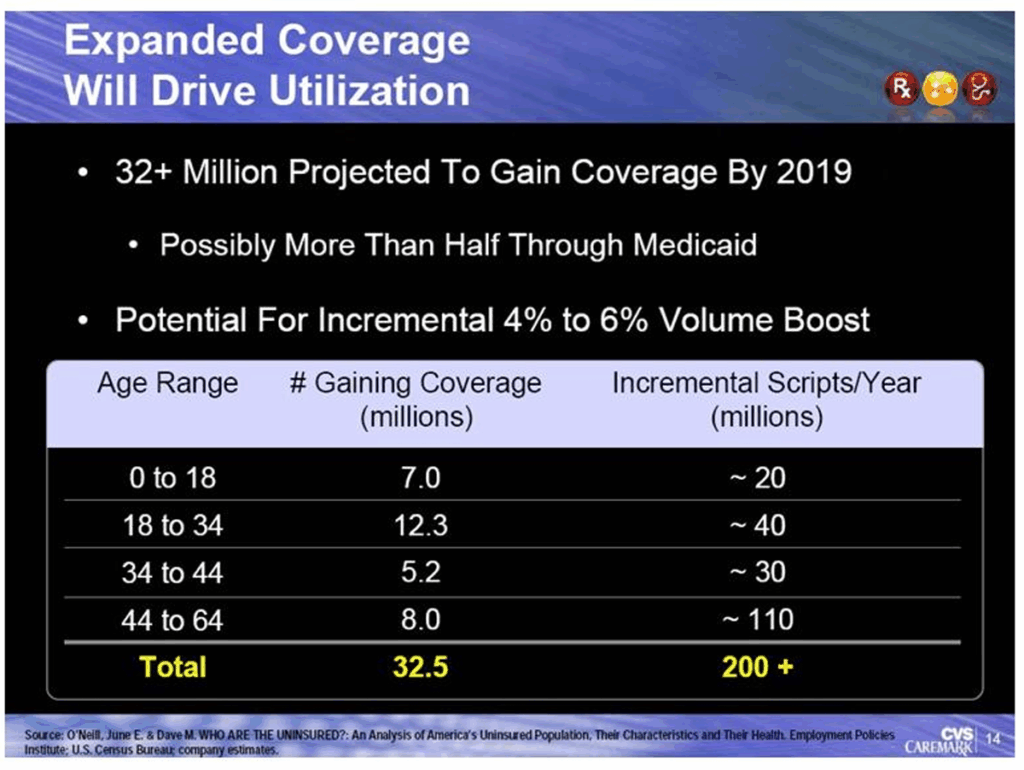

In addition to growth in the Medicare population, CVS is well positioned to benefit from an estimated 32 million people expected to gain insurance coverage as a result of healthcare reform. Beginning in 2014, healthcare reform will expand Medicaid eligibility and will provide subsidies to purchase insurance on newly created health insurance exchanges. We look at the expansion of coverage in healthcare reform as a free option. If it hits, it could provide a 10% bump to the 636 million scripts CVS dispensed in its drugstores in 2010 and add 17% to CVS‘ current earnings. (CVS’ 18% market share x 32 mm people x 1 Rx per person per month x 12 months x $9 incremental after-tax profit per Rx = $0.45 per share.)

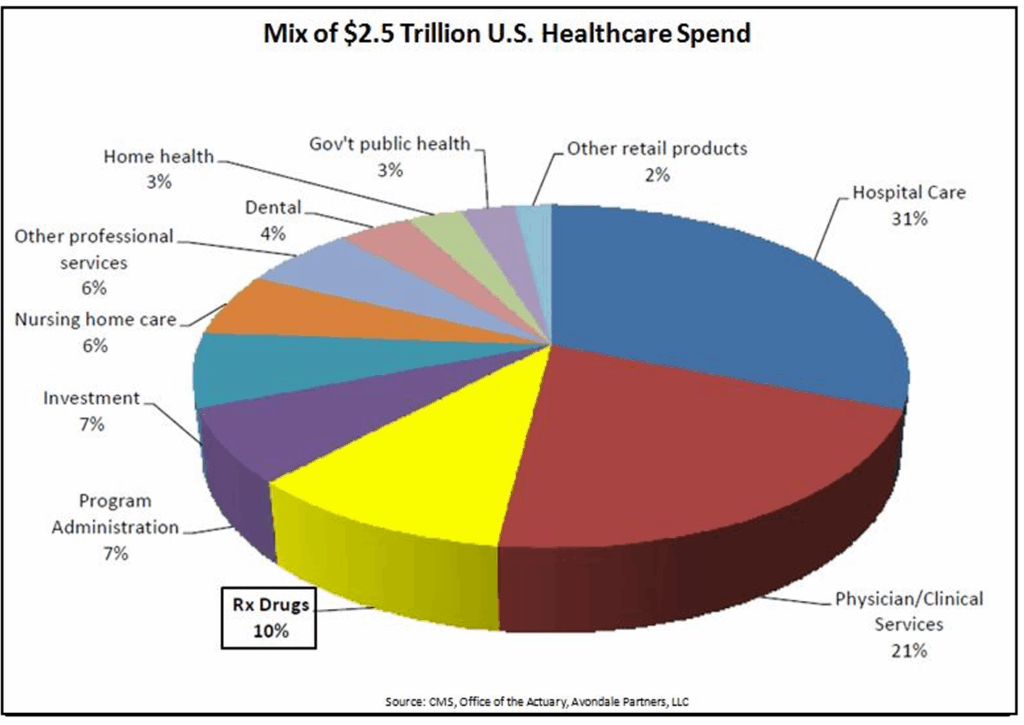

We don‘t know what health care reform will ultimately look like, but we take some comfort in the knowledge that prescription drugs represent just 10% of the total health spend and that increasing patient adherence to drug regimens is among the most cost effective ways to lower medical costs.

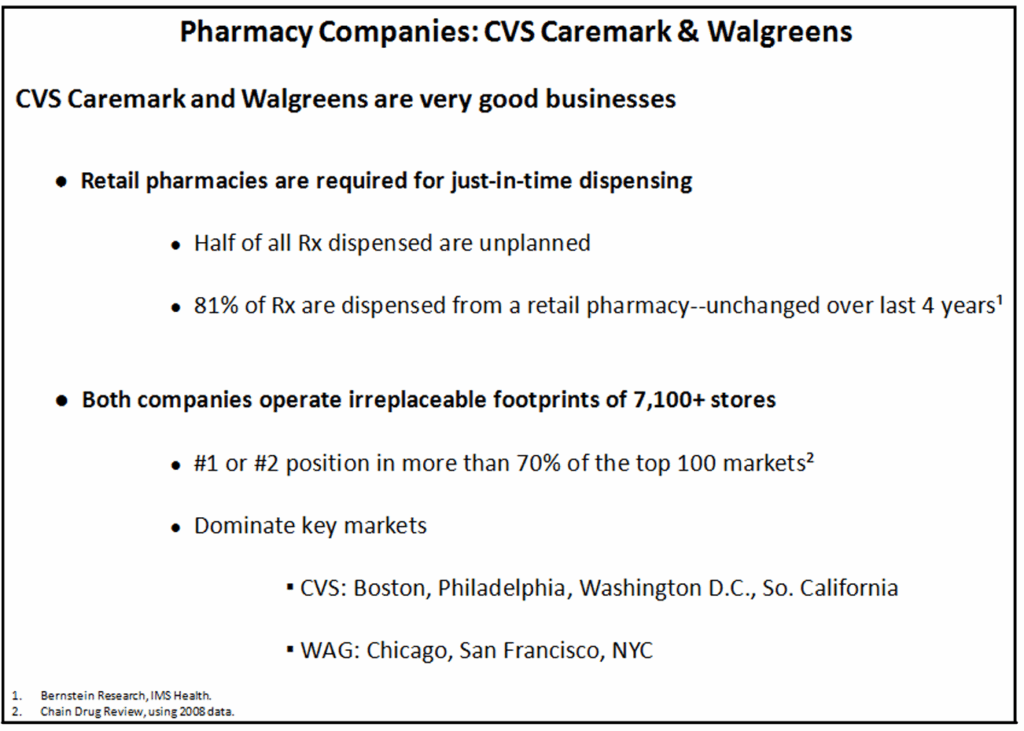

The pharmacy companies, particularly the two largest national chains, are well-positioned to benefit from those trends. With half of all Rx dispensed being unplanned, retail pharmacies are a necessity for just-in-time dispensing. Retail pharmacies dispense 81% of all prescriptions – a share that‘s been unchanged over four years. Among pharmacy retailers, CVS and Walgreens are the best positioned, with each company operating more than 7,000 stores and ranking either #1 or #2 in 70% of the top 100 markets. CVS has a store within three miles of 75% of the population, and fills 18% of U.S. retail prescriptions. We expect that CVS and Walgreens will continue to gain share in a growing market, particularly from the smaller independents whose market share has been halved in the past couple of decades to its current 20%. The third largest national chain is Rite-Aid, but that company isn‘t much of a threat because it‘s highly leveraged, has a third lower sales per square foot, and fulfills less than half the number of prescriptions dispensed by either CVS or Walgreens.

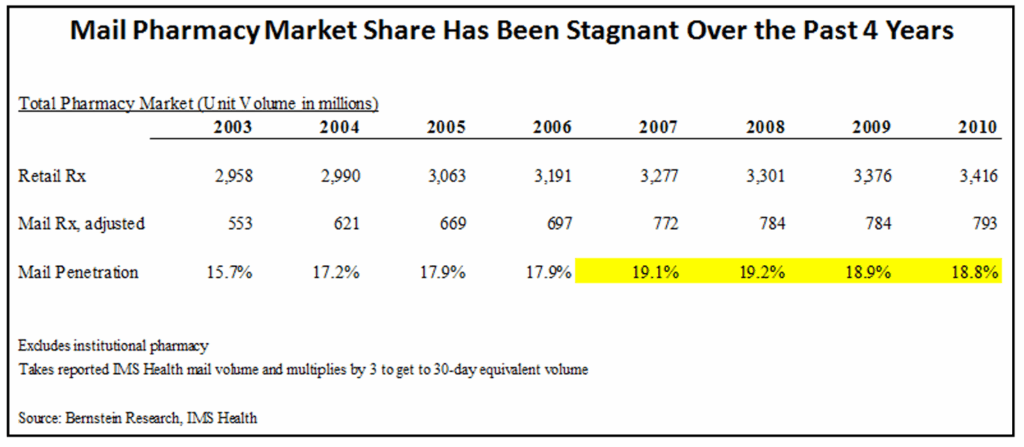

There has been some concern that mail order will erode walk-in business. We expect that may have some small impact over time, but over the last four years, mail order‘s share of the market has remained at a relatively constant 19%.

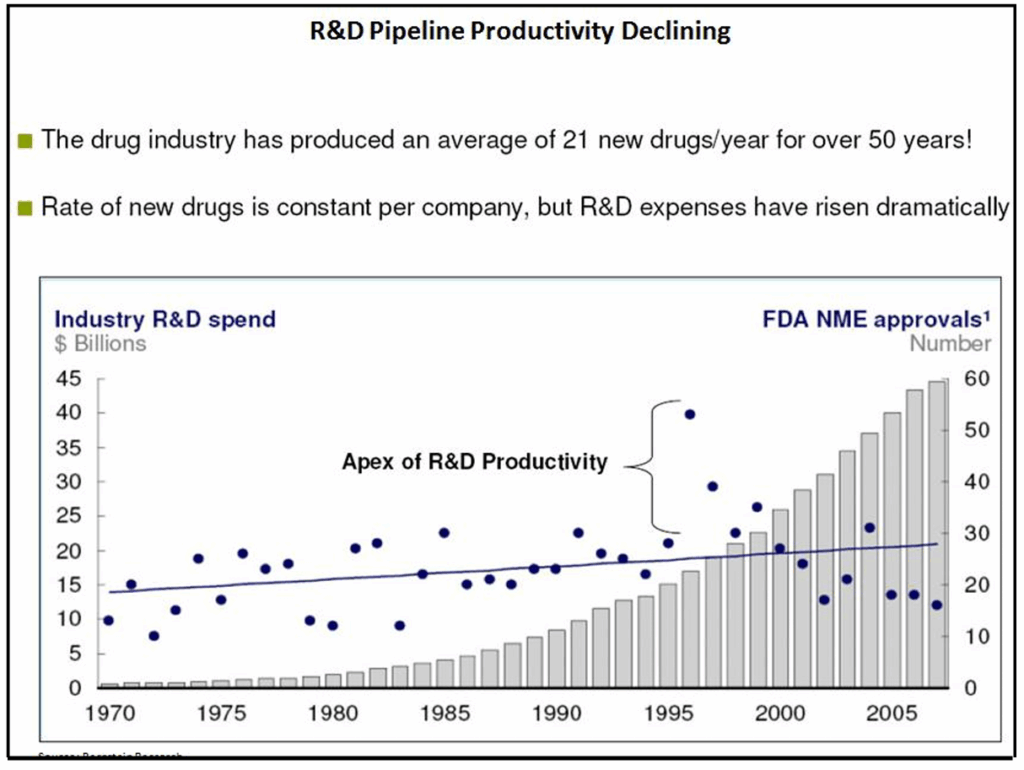

The peak of Big Pharma‘s productivity occurred in the mid-90s, and those drugs are now facing the end of their patent lives. Note that the R&D spend is almost 6x what it was in 1990, but the number of approvals is lower. This speaks to the fundamental challenges facing Big Pharma today.

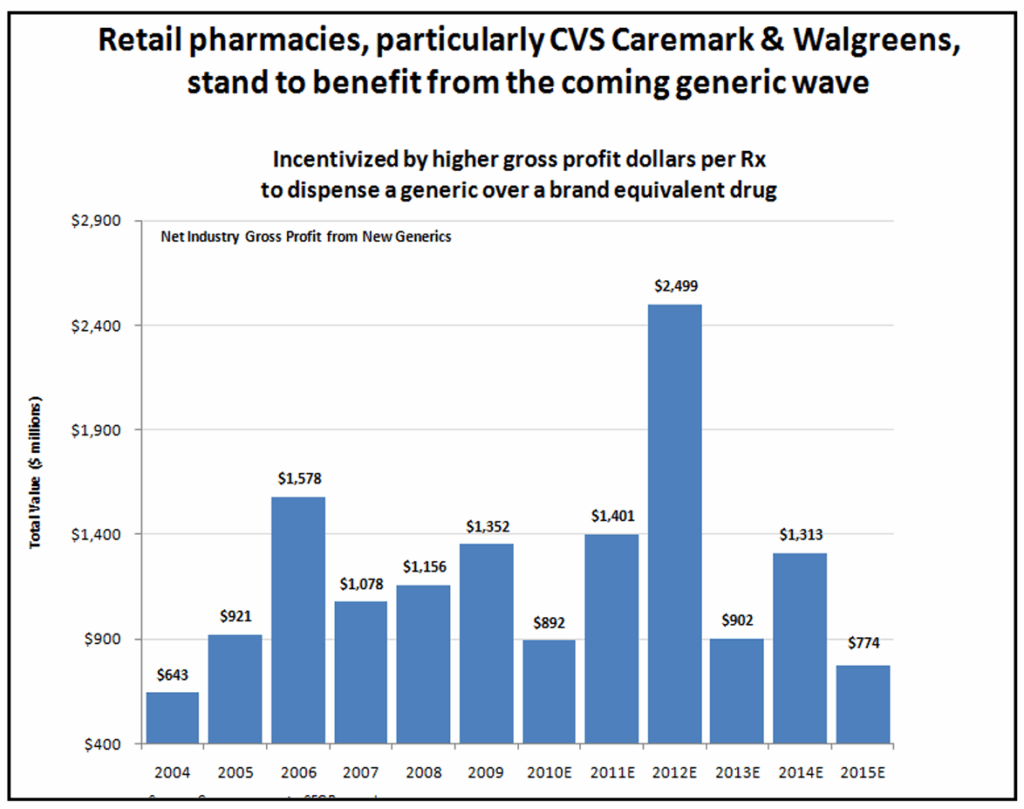

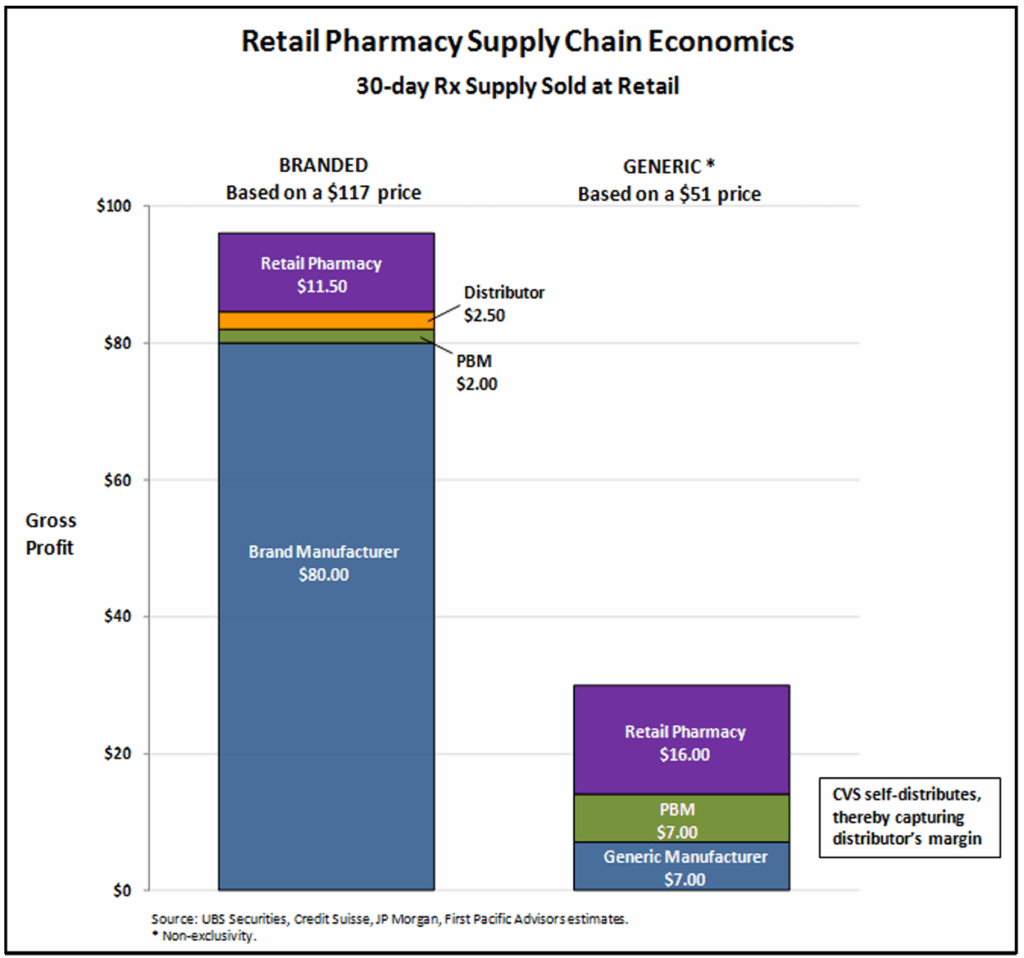

Retail pharmacies should enjoy better margins from the coming generic wave that‘s due to peak in 2012, since they make more money selling generic drugs than branded.

The margin expansion comes from both having more vendor options and since they self-distribute capturing the distributor margin for themselves on every prescription. In this example, unit gross profit expands at CVS‘ pharmacies, from $11.50 to $16.00, a 39% increase.

CVS has become a brand unto itself, and with that, private label opportunities will continue to proliferate. Private label products offer CVS a better gross profit opportunity on every sale. At my local supermarket, I buy Thomas‘ English Muffins because the private label version lacks the nooks and crannies. In general, I‘ve found that consumers are more willing to switch to a private label item if it is something they can‘t taste. Medication certainly falls into that category. I now buy the little blue pills that are CVS‘ substitute for Aleve, as well as the CVS brand multi-vitamin instead of Centrum, and I find their sunscreen works fine as well. The production issues and recall problems at Johnson & Johnson are adding momentum to the trend. CVS expects its private label business will rise to 20% of overall revenue in the next two to three years, up from 17% today. Private label sales hurt comparable store sales because the average price can be 15% to 20% less than for the equivalent branded product, but gross margin can be ten percentage points higher, leading to a gross profit dollar increase of about 10%. We believe the increase in private label over the next two years could increase retail operating income by 3.5%.

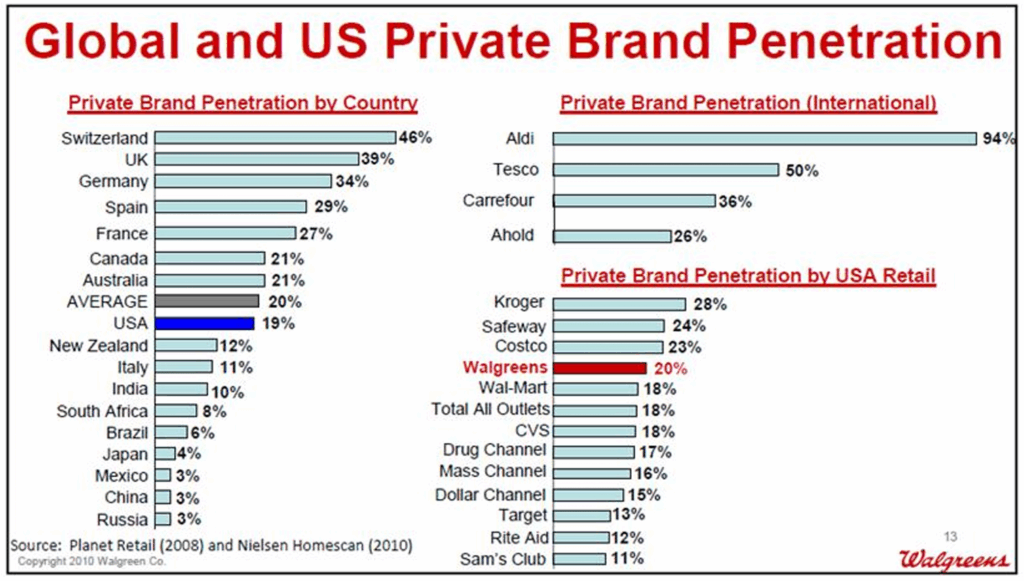

This still leaves a ton of room for private label expansion. U.S. retailers like Kroger have 28% private brand penetration, which pales next to UK-based Tesco‘s 50%. This leaves CVS a lot of runway for years to come.

We would be remiss not to talk about Caremark, CVS‘ Pharmacy Benefits Manager, since it represents almost half of CVS sales and a bit more than one-third of its profits. For those of you less familiar with the industry, a Pharmacy Benefits Manager, or PBM, is a third-party administrator of prescription drug programs. Among other services, PBMs aggregate the buying power of their many large customers to obtain lower prices from drug manufacturers and induce pharmacists to switch from brands to generics, thereby lowering costs in the supply chain. Caremark fills or manages 20% of all U.S. scripts, serving a network of 64,000 pharmacies and covering 53 million lives. They are the second-largest mail order pharmacy after Medco, but they lead the market in Specialty Pharmacy and Generics.

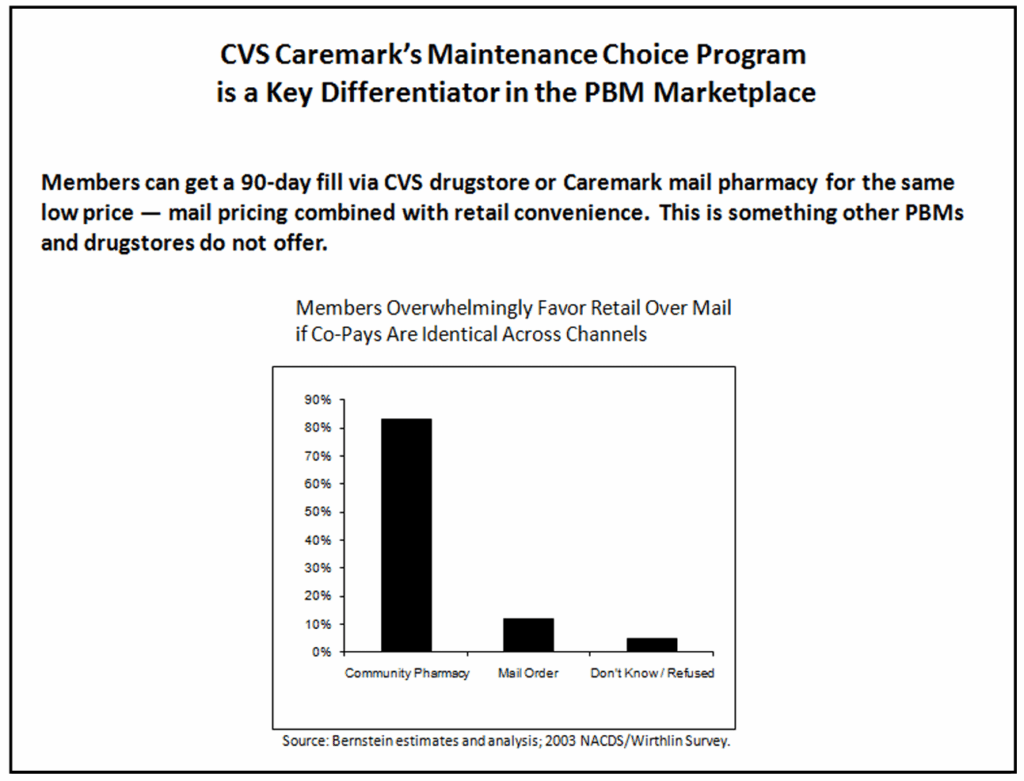

Having both a PBM and a retail business allowed Caremark to introduce its Maintenance Choice program, differentiating it from the competition. With this uniquely integrated model, customers can get mail order pricing and still pick up their prescriptions in a CVS store – something other PBMs and drugstores don‘t offer. It‘s a great benefit for people who get caught short of necessary meds because they forgot to refill their 90-day prescription, or because it got lost in the mail. Only 15% of Caremark‘s members use Maintenance Choice today, leaving an addressable opportunity of another 42%, which should lead to additional share gains, particularly at the expense of independent pharmacies.2

In addition to the opportunities, however, we see some challenges facing the PBM space, including the possibility of lower future rebates, the introduction by Medicaid of legally mandated transparency of drug acquisition costs, and challenges from traditional health insurers in specialty pharma. As a result, we‘ve chosen to hedge out a piece of the PBM exposure. The hedge allows us to still benefit if Caremark outperforms its rivals over the next few years (as we believe it will) and gives us some protection should headwinds erode industry profitability.

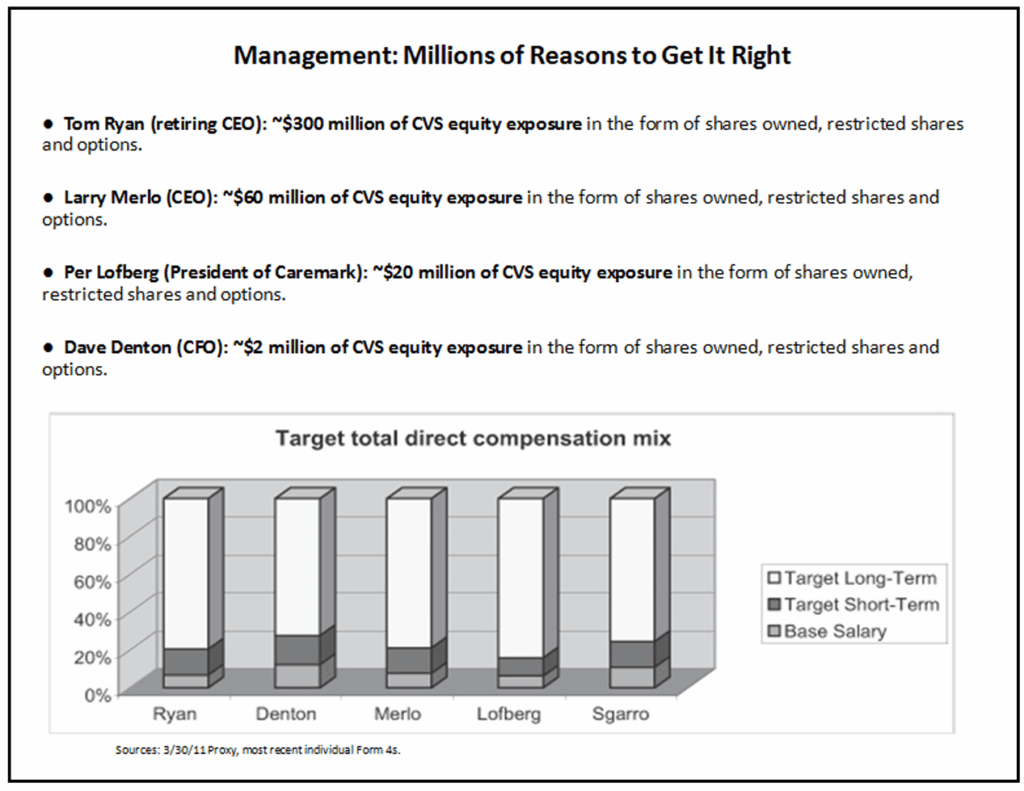

CVS‘ executives have proven themselves to be skilled operators as well as prudent capital allocators. Their attention to the wise use of cash makes sense because they‘re invested alongside us. In fact, CVS‘ management has millions of reasons to get it right. Tom Ryan, the retiring CEO, has about $300 million of CVS equity exposure, and three other top executives have a combined exposure of more than $80 million.

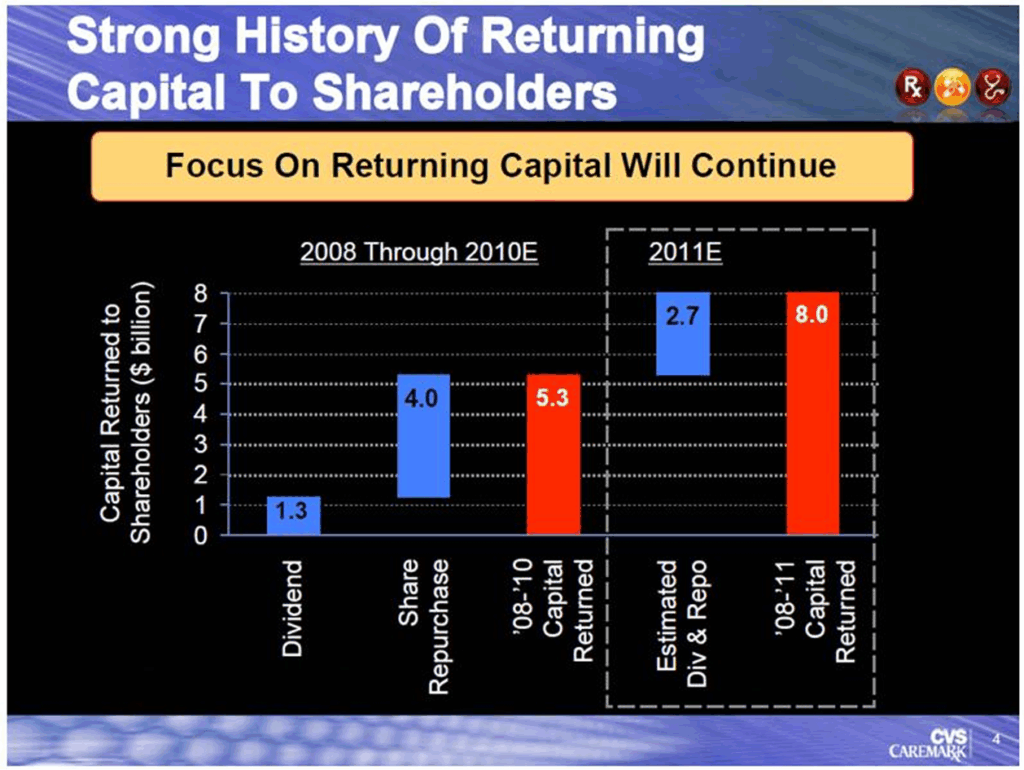

By the end of this year, CVS will have returned almost $6 per share in capital to their shareholders, or approximately 18% of their average market capitalization, in the four years since 2007. If you were to add debt repayment to this, the equity benefit would be 20%. CVS has publicly stated that it intends to spend $3-4 billion per year on share repurchases. Add in the dividend, and you get 7.5-9.5% per year in cash used to enhance shareholder value. The cumulative free cash flow over the next five years should exceed 50% of the current market capitalization, and the majority of that will be returned to shareholders.

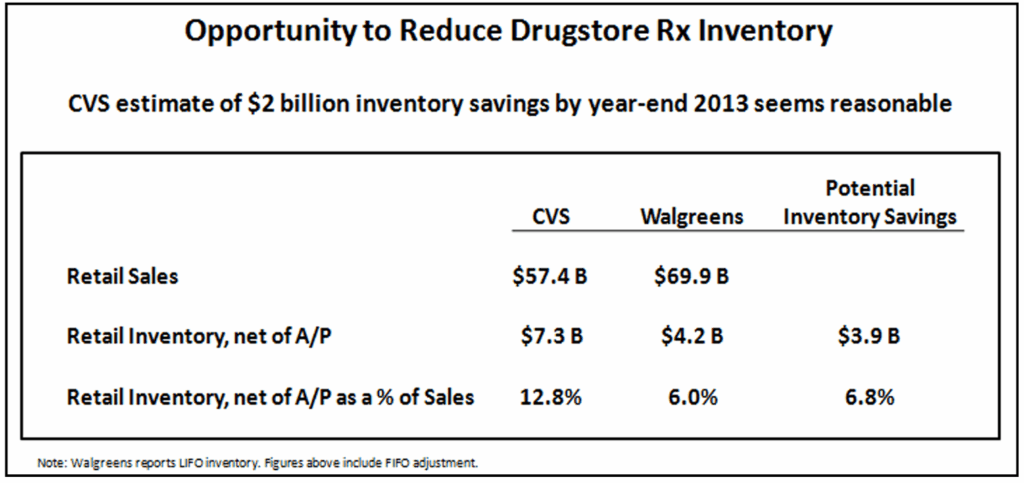

We also think the current valuation ignores what could be significant working capital improvements. CVS grew through acquisition, and it still isn‘t where it needs to be. For example, each distribution center (DC) serves only 378 stores compared to the 473 stores that run through the typical Walgreens DC. In 2010, CVS operated with seven inventory management systems, while Caremark had five different claims platforms. By 2013, their goal is to be down to one platform each. The company has said it can reduce retail store inventories by $2 billion over the next three years, representing about a $1.50 per CVS share, or 4.2%. That seems reasonable, since the company‘s retail business has almost 13% of its sales tied up in inventory net of payables, compared to Walgreens‘ 6%. We are not suggesting that CVS is likely to achieve Walgreens‘ efficiency anytime soon, but it does lend some comfort to the company‘s guidance.

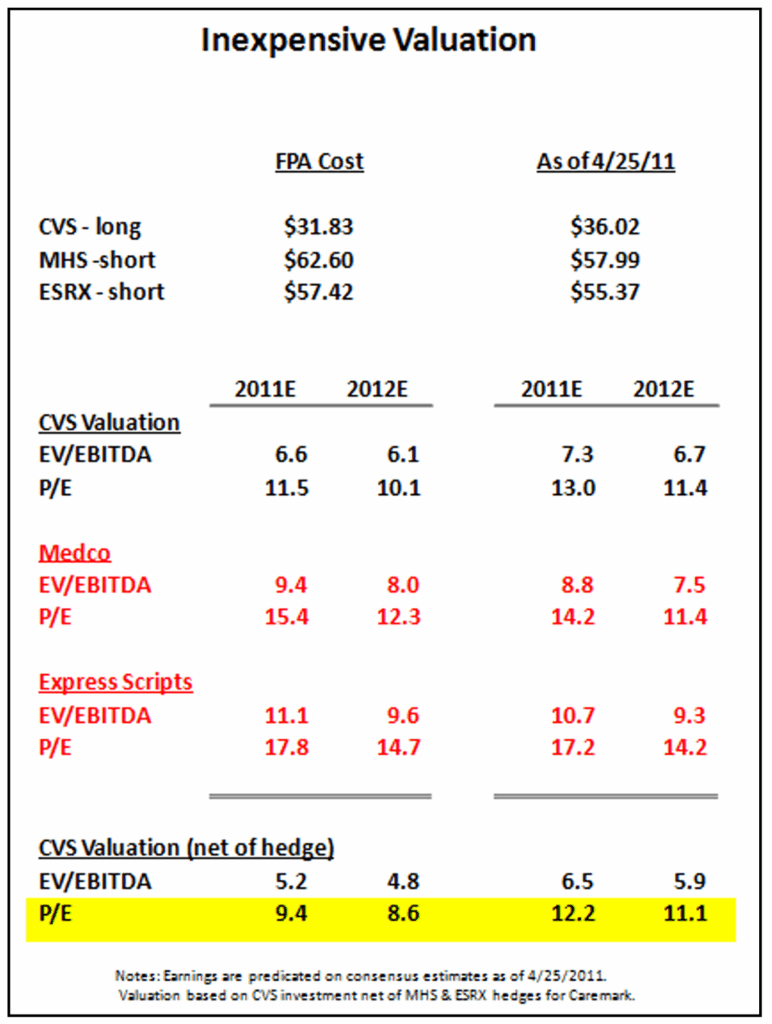

When we first purchased CVS in 2010, it was trading at about 11.5x 2011‘s earnings. We felt the valuation adequately compensated for our concerns regarding their PBM business – as well as for our admittedly less robust understanding of its prospects. As CVS‘ stock price began to tick up, the PBM comps, Medco and Express Scripts, moved up even more, reducing the price of the CVS retail stub.

Using the PBM competition as a comp, we felt, at that time, that the Caremark value attributable to the total enterprise was about 46%. On that basis, the CVS stub traded to just 9.4x free cash earnings. We therefore ended up hedging a portion of the PBM exposure – to capture the lower valuation as well as to eliminate some of the risk and accompanying discomfort of what we don‘t know regarding the PBM business. At this point, we still have some PBM exposure, albeit reduced. We believe that Caremark can outperform its peer group as it is now being better managed by Per Lofberg, the former Medco head as its President, and is poised to benefit vis-à-vis its competition. Contributing to this will be better customer service, the aforementioned systems improvements, as well as the competitive advantage of their Maintenance Choice integrated model.

There has been some recent chatter about CVS potentially selling or spinning off Caremark to increase shareholder value. We believe there is a lot of opportunity to improve their PBM business and would prefer giving the new management team a couple years to execute on their plans. However, if Caremark ultimately fails to perform to its potential, its sale to a strategic buyer such as Medco or Express Scripts could be in the best interest of shareholders. One would then have to analyze how the benefits that currently accrue to each can be maintained. I have not yet seen evidence to support the argument that a spin-off would add much value, particularly since the combination of Caremark and CVS‘ businesses created the differentiated Maintenance Choice program and preserving that program after the spinoff or sale might prove problematic.

Since we decided to talk about CVS a month ago, its stock price has moved up, so I thought it important to reflect a more current valuation. Unhedged, the stock still seems reasonably priced at 13.0x 2011 earnings and 11.4x 2012‘s — hedging the PBM exposure creates the stub retail business at about 12x 2011 and 11x 2012 earnings. I wouldn‘t characterize CVS as any kind of homerun stock but it should nevertheless prove to be a solid compounder over the next few years as the aforementioned macro tailwinds begin to blow and are recognized by other investors.

And now for our gold play… Well, not really, but there is gold in its name. Goldlion.

Goldlion, a $400 million USD market cap company (but with the free float at just one-third that), is a Hong Kong based apparel company that largely sells into China, with a small amount of revenues derived from Singapore & Malaysia (11%). They have a ―mass affluent‖ brand that‘s in the same league as Coach or Polo, but not Chanel or Gucci. Goldlion sells most of its merchandise to the distributors who run the counters in department stores. They also have a few directly-owned stores and a small licensing business.

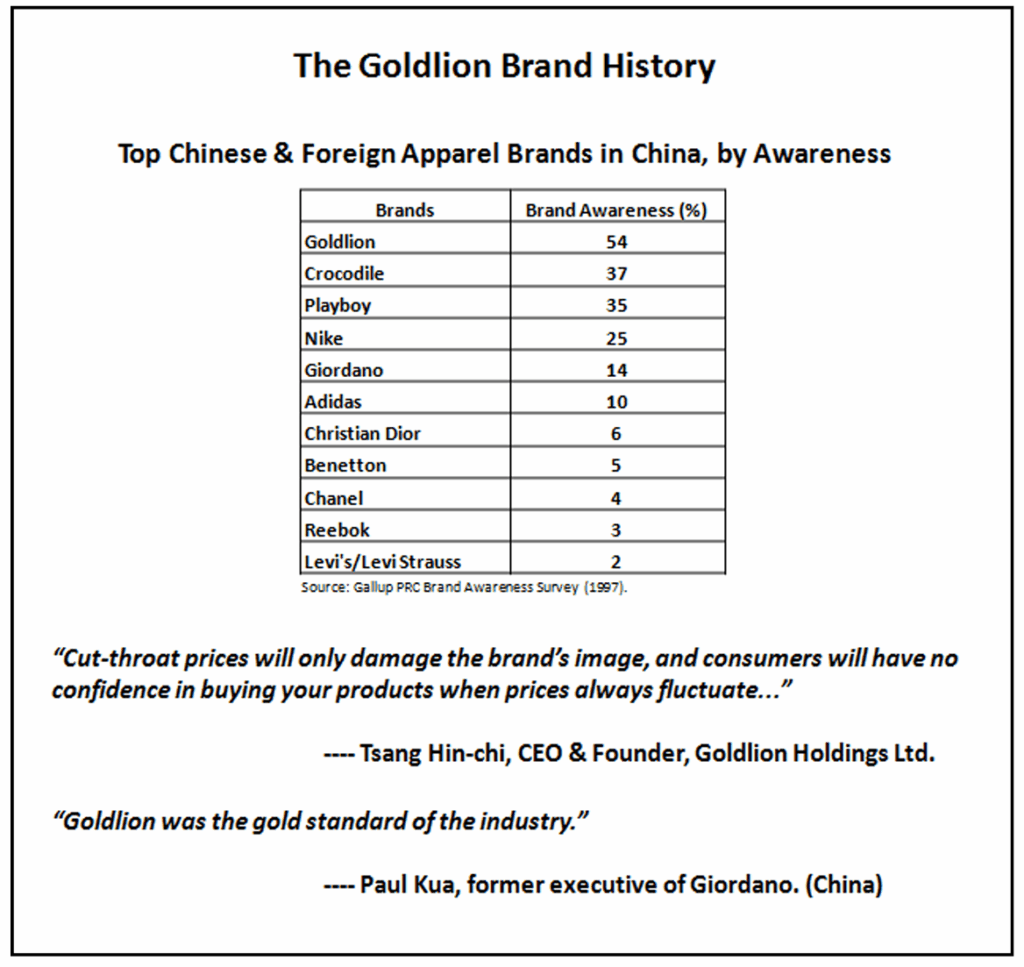

The company was founded in 1968 and entered the Chinese market in the mid-1980s, gaining the distinction as the first foreign apparel brand to directly operate in that country. In 1997, it was the #1 apparel name in China, as measured by brand awareness. This once iconic, but still relevant brand maintains quality over all else. The CEO never compromised, recognizing that “Cut-throat prices will only damage the brand‘s image, and consumers will have no confidence in buying your products when prices always fluctuate…”3 Goldlion earned the respect of its peers, and has been described as the “gold standard.”

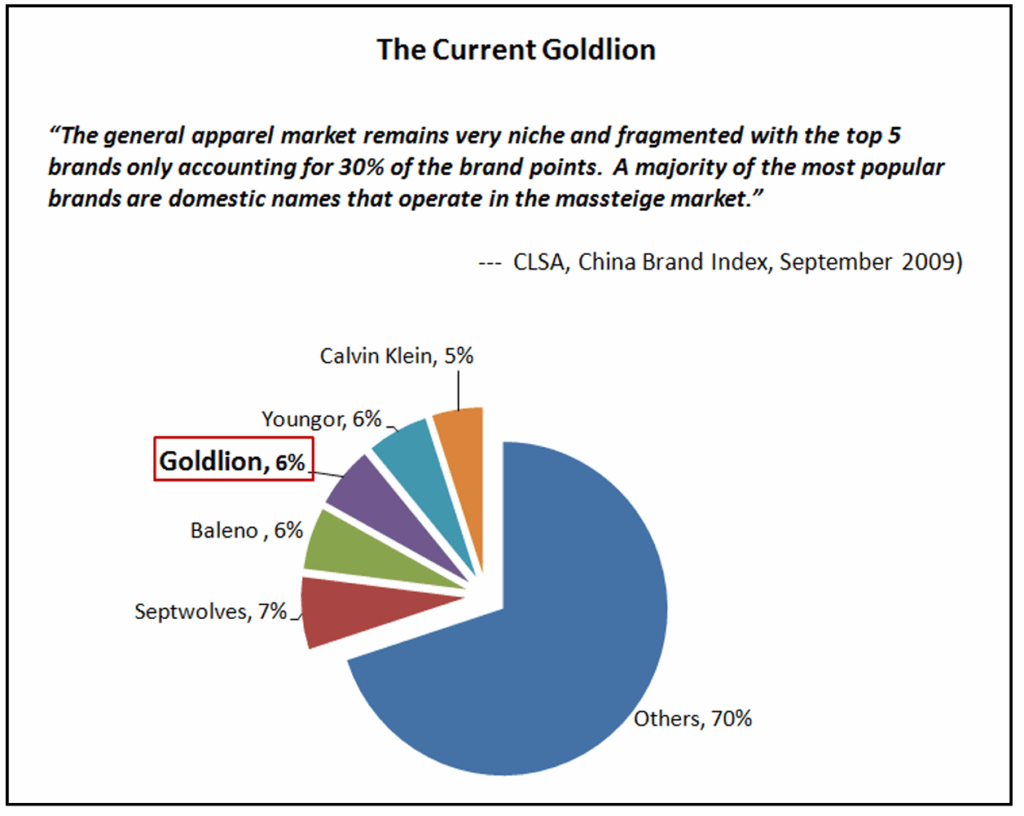

Goldlion lost its way in the late 1990‘s, but the company recognized it and brought in a new CEO at the turn of the century. It remains an important player today, with 6% market share – one of the largest in China‘s fragmented apparel market.

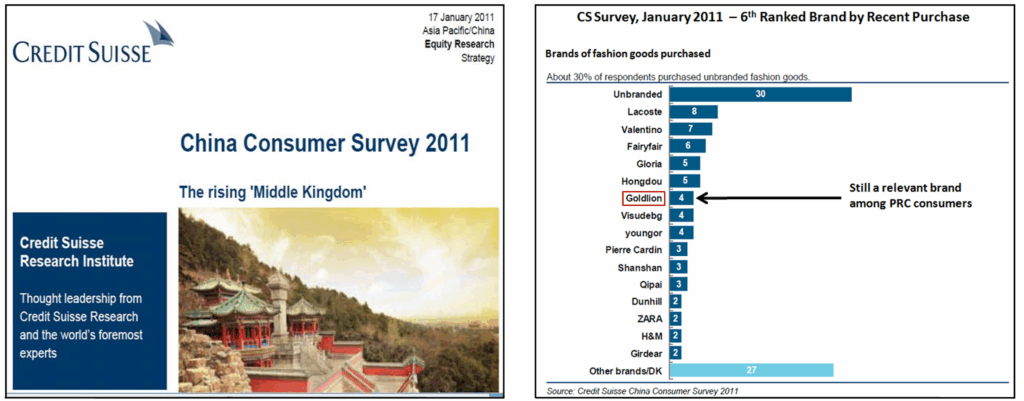

In January, a consumer survey by Credit Suisse ranked Goldlion 6th among recently purchased branded fashion goods.

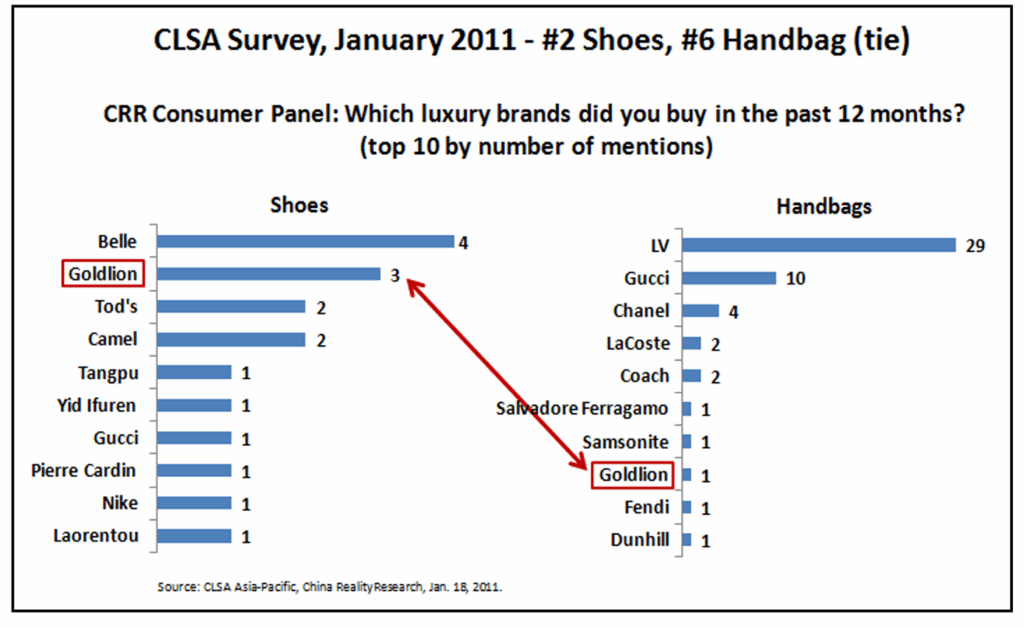

A recent CLSA survey also reflected Goldlion‘s brand strength, particularly in shoes, where the company is #2. The brand is tied at #6 in handbags, where the company has a smaller presence.

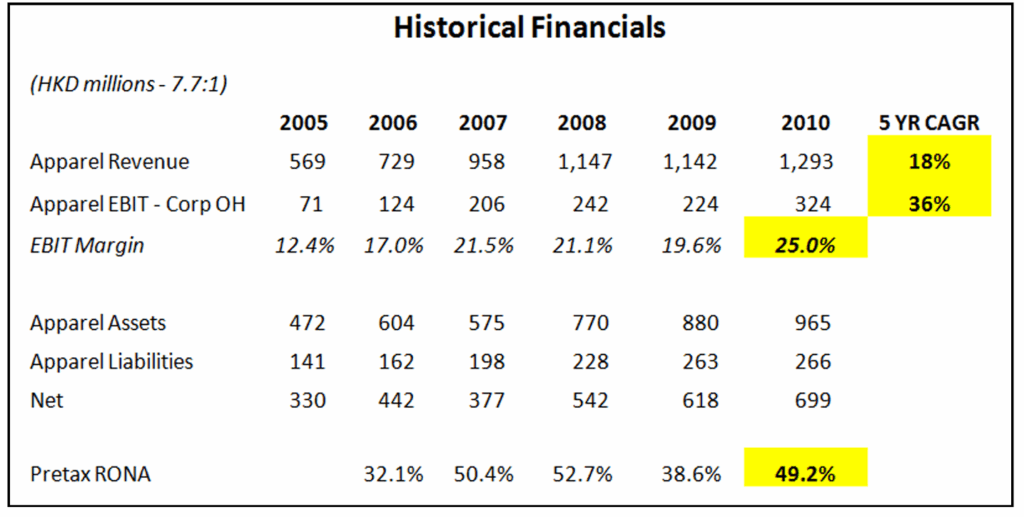

Goldlion is a rapidly growing business, with high margins and a high return on capital. Revenues have increased at an 18% compounded rate over the last 5 years, and income has grown even faster, at a more than 30% rate. Operating margins are 25% and pre-tax return on net assets is almost 50%.

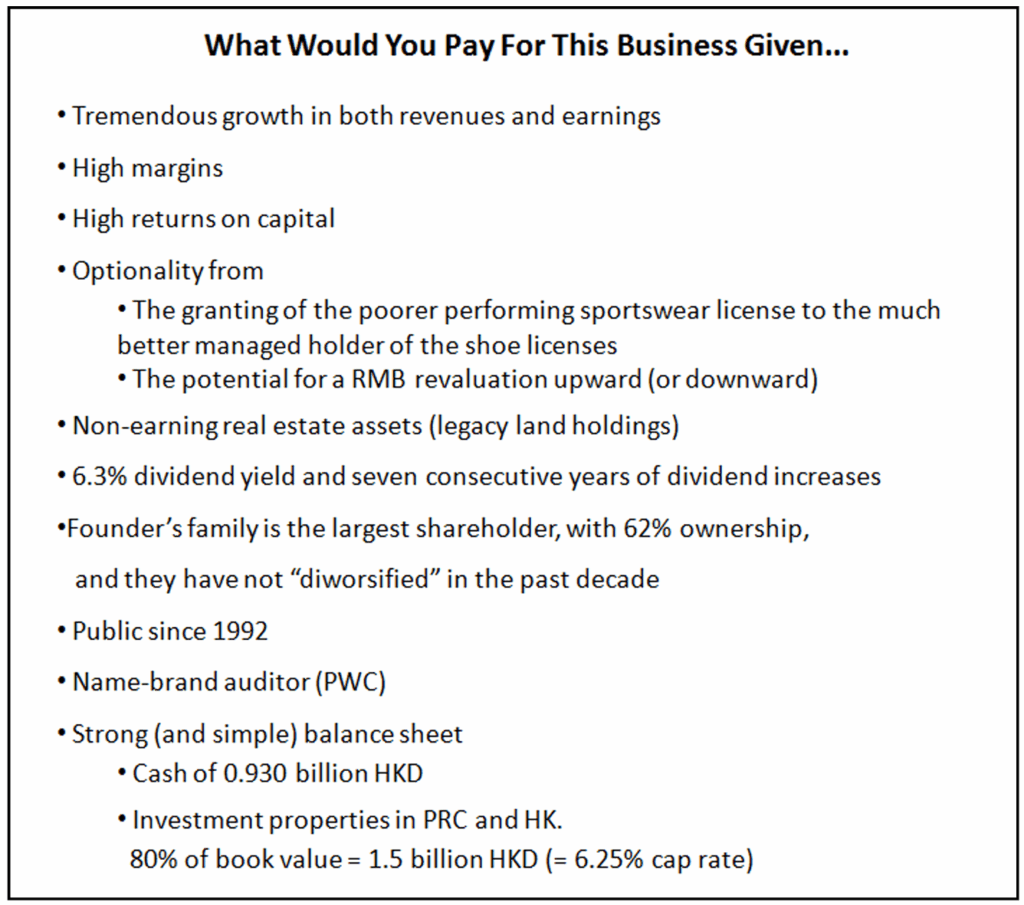

What Would You Pay For This Business?….Given tremendous growth in both revenues and earnings, high margins, high returns on capital, as well as optionality from the transfer of the underperforming sportswear license to the better-managed holder of the shoe licenses. There‘s also the potential for a RMB revaluation upward (or downward) and the monetization of non-earning real estate assets (investment properties in PRC and HK that we value at 80% of book value, or 1.5 billion HKD (a 6 ¼ % cap rate)), plus a 6.3% dividend yield, and seven consecutive years of dividend increases. Consider these factors as well: the founder‘s family remains the largest shareholder (62%), the company has not ―diworsified‖ in the past decade, and that Goldlion has maintained a public listing since 1992, has a name-brand auditor (PWC), and a strong (and simple) balance sheet with cash of 0.93 billion HKD.

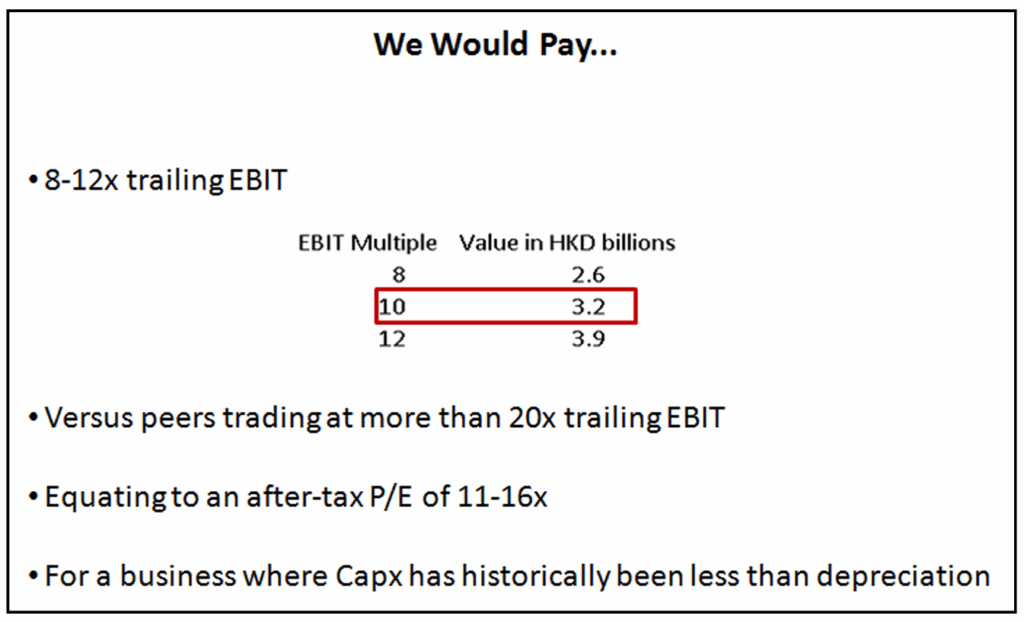

We would pay 8-12x trailing EBIT for Goldlion (whose peers are trading at more than 20x trailing EBIT), amounting to an after-tax P/E of 11-16x, for a business where Capex has historically been less than depreciation.

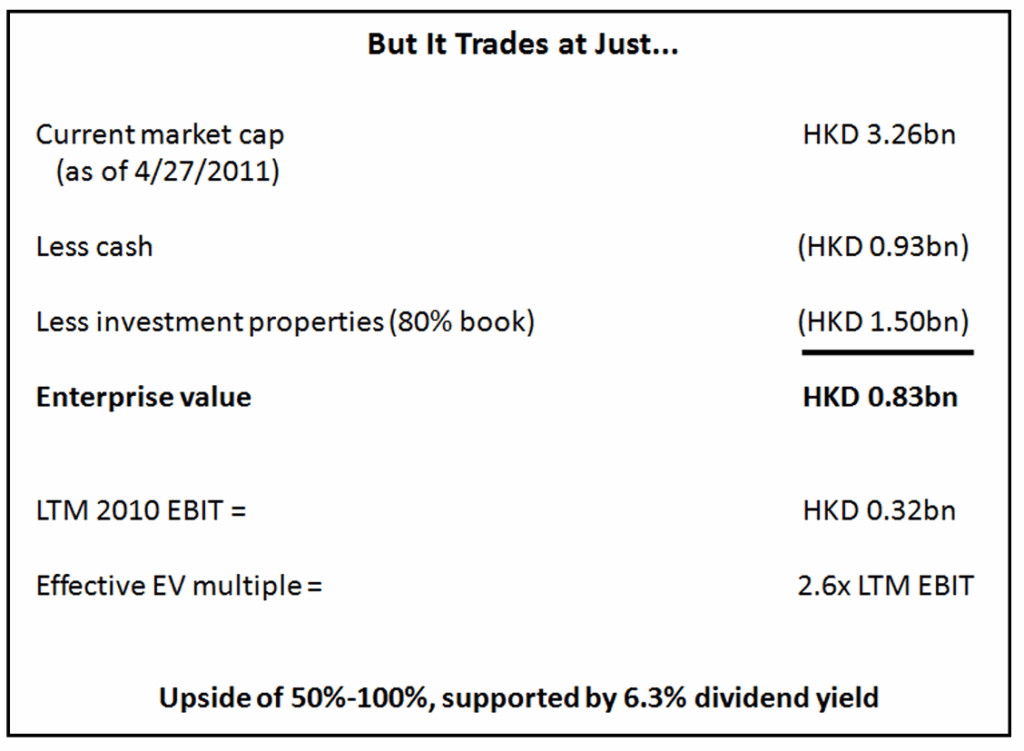

Yet Goldlion trades at just 3.26 billion HKD (current market cap), which, if you were to use our apparel matrix from the prior slide, would place fair value in the range of 5.0-6.3 billion HKD. You can then subtract the cash and investment properties to derive an adjusted enterprise value (EV) of just 0.83 billion HKD. With the company delivering last twelve months EBIT of 0.32 billion HKD, Goldlion seems pretty inexpensive – an effective trailing EV multiple of just 2.6x. We therefore believe there‘s potential upside of 50-100%, not counting the company‘s 6.3% dividend yield.

In closing, as Lewis Carroll once said, ―If you don‘t know where you are going, any road will get you there.‖ I wrote in our FPA Contrarian Policy Statement that, ―We are value investors because it makes sense to us, fits our risk averse personalities, and appeals to our sense of intellectual honesty. We believe that value investing is the best means (that we are aware of) to preserve capital and to continue to provide adequate growth over the long term.‖ I urge you to know yourselves as investors, and to be aware of your strengths and weaknesses. We all have both. Let thoughtfulness and patience be your guide to achieving your long-term goals and don‘t allow yourself to be swayed by either the quick buck or short-term market movements.

Thank you.

Steven Romick

1Discount versus average since 1930.

2The addressable market is 57% of total Caremark members because unions, government employees and other clients won‘t accept ―restrictive‖ plans. Maintenance Choice isn‘t restrictive, but it can come across as pushing CVS over independent community pharmacies.

3Hong Kong iMail, “Goldlion bets big on style, design revamp,” August 31, 1999.